After last week’s Nostalgia Album sadness at hearing great aunt Ernestine lost her husband in the First War, her son in the Second War and spent much of her life in the Lancaster County Mental Hospital, we need cheering up.

Previously, I have hinted at sunnier climes. Here they come. We shall return to the interesting war service of Alf (my great uncle by marriage) but before that we will allow ourselves to be distracted to a much more hospitable climate than post-war austerity Britain with its record-breaking harsh winters.

© Always Worth Saying 2022, Going Postal

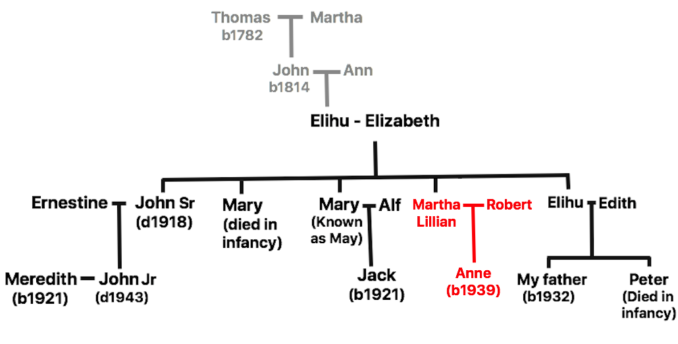

My father’s second oldest aunt was called Martha Lillian. Martha is a name that enters the family after a Martha married my great-great-grandfather, Thomas, a farmer of 150 acres. Martha’s family were Quakers. She had a brother called Elihu, a name she brought with her when her eldest son was Christened. My grandfather and great grandfather were also called Elihu.

One of her daughters was Christened Martha and married into a family that included brothers Shadrach, Meshach and Solomon, after the King of Isreal and the builders of his temple in Jerusalem. Meshach and Martha emigrated to Australia, helped to found the state of Victoria and brought Christianity to the aboriginals. But that’s another story.

For the time being, we will follow my great aunt Martha Lillian, often known as Lillian or Lil, who was born in late 1898. Eighteen at the end of the war, she belonged to a generation of young women whose chance of their own family life was disrupted by the sacrifice of the trenches.

Not marrying until 1934, at the ripe old age of 35, daughter Ann (my father’s cousin) was born in July 1939 just before the outbreak of the second war, by which time Lil was 40.

In a 1938 local newspaper article about my great grandparent’s golden wedding, she is described as a married woman of Bassenthwaite Street – another tightly-knit, spotless, working and lower-middle-class neighbour in the factory district of Carlisle.

In the government’s 1939 Residency Survey, husband Robert is employed as a ‘bricklayer, heavy worker’ and is aged 33, seven years her junior. He is also an Air Raid Warden while Lil is occupied in unpaid domestic duties.

During the war, the generations changed. My great grandmother Elizabeth died in 1940, aged 73. My great grandfather passed in 1944, during his 84th year. Their grandson, John Jr, was killed serving his country in Bône, Algeria, in 1943.

© Always Worth Saying 2022, Going Postal

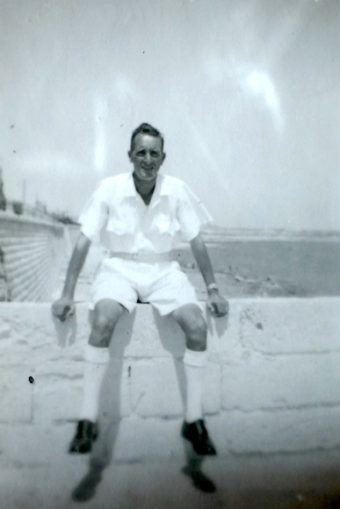

As well as volunteering as an Air Raid Warden, Robert was to volunteer for the Navy. The reverse of this photograph is captioned ‘July 9th 1944’ and ‘All the best, Rob’. Obviously, it was sent from an overseas posting.

Painfully thin but in good order with spotless whites and shiny shoes, it is also captioned ‘Ghar id Dhud, Sliema’ which, as every Puffin knows, is in Malta. Not the easiest of wartime postings but, by July 1944, nearby Italy had surrendered and the war will have felt far away.

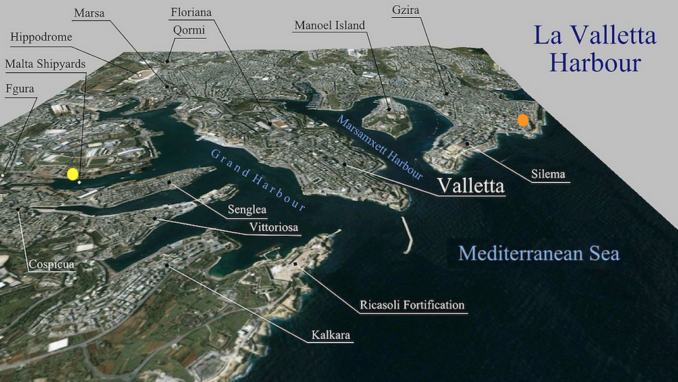

Sliema sits on Malta’s eastern coast, above the harbour of Marsamxett below which lies the more well-known town of Valletta, to the south of which is Malta’s Grand Harbour and naval bases. Ghar id Dhud is still a main street in Sliema, but reference to old postcards suggests the area previously included the coastal promenade that was the place to stroll and to see and be seen.

Prelucrare 3D pentru La Valletta Harbour.,

Asybaris01 – Public domain

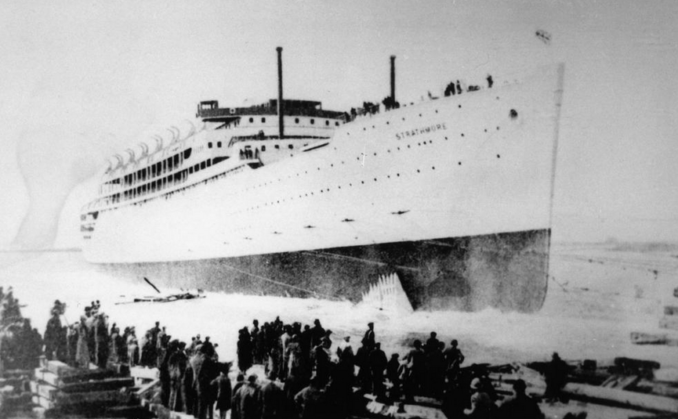

After the war, escaping post-war austerity Britain and its dreadful weather, a ship’s manifest shows Lillian and six-year-old Ann setting off to join Rob. They embark on P&O’s SS Strathmore (at the time, still commandeered by the government) with their declared intended permanent residence being Malta.

With Captain A. Rogers at the helm, the Strathmore was a 23,428-ton vessel, launched by the Queen Mother (Elizabeth, Duchess of York as she was then) in Barrow-in Furness in 1935. It was one of five ‘Strath’ class sister ships built to connect Blighty with India, the Far East and Australia.

Launching of the Strathmore,

Photographer unknown – Public domain

Used as a troop carrier during the war, in the early post-war years it continued in government service and on the 9th February 1946, as Lil and Anne walked up the gangway, Strathmore was en-route to Japan with a port of call in Malta.

There, Rob, Lil and Anne had accommodations in Amery Street, Sliema, the orange dot on the aerial photograph above. The property is still there and has the same front door!

© Always Worth Saying 2022, Going Postal

Albeit, an electric door buzzer has replaced a bell pull and the frontage of the house next door has been ‘improved’ with some Maltese wiring.

The street runs northwards until the seafront at Tower Road, presumably so-called because of a series of small coastal watchtowers built around the island by the Knights Of Malta in the 17th century. The two-story Victorian terrace, with its bay windows and shutters, hasn’t survived, the locale proving irresistible to the developers of blocks of concrete flats.

© Always Worth Saying 2022, Going Postal

© Always Worth Saying 2022, Going Postal

Their new home appears to have been idilyic with airy high ceilinged rooms, separated by curtains, containing fine cabinets displaying porcelain dinnerware and topped with lots of books.

Slender double doors, guarded by sunscreens, led to a courtyard. They had the use of a car, a shiny Ford Prefect, registration number 1081, pictured gleaming outside the Amery Street property. An impressed little girl looks on.

© Always Worth Saying 2022, Going Postal

© Always Worth Saying 2022, Going Postal

I’ll tell you something, Puffins. If this humble author ever disappears, he will be found down at the docks with a one-way ticket to Malta. A newspaper will be tucked under his arm with a circle drawn around a job advertisement reading ‘Sliema. Royal Navy foreman wanted. Apply in person.’

Being an island, as the low registration number suggests, expensive to import motor vehicles were rare with local transport being provided by donkey and cart. With their packed narrow streets, Sliema and Valetta were famous for their street vendors and carts.

In Maltese, these are called “bejjiegħa tat-toroq” and would sell food and household goods, in fact, anything and everything. They even provided entertainment.

© Always Worth Saying 2022, Going Postal

The above photograph shows a grinder playing music for the local Navy family children. The upper part of the display consists of flags, the lower seems to be hung with dolls. I wonder if they danced mechanically in time with the music? The photograph is taken in Amery Steet, just outside the family property with the background still being recognisable today.

The closest house to the right has been replaced with one of breezeblocks and concrete but the others are refreshing as they were.

As hinted at above, Rob is documented as a Royal Navy foreman. His subsequent postings, his previous employment on building sites and him being a big lad suggests he worked in the shipyards at the naval base.

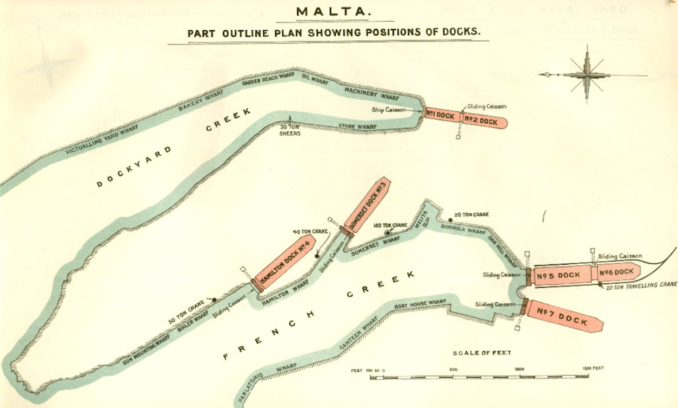

Malta. Part outline plan showing position of docks. 1909,

British Admiralty – Public domain

The Knights of Malta built the dockyards for their galleys. The Royal Navy took over the facilities in 1800 when Malta became a British protectorate. By 1909 numerous wharves and dry docks had been built along Dockyard Creek and French Creek off the Grand Harbour – the yellow dot in picture three.

The names of the various harboursides give an idea of what went on in the dockyard. Not only was there Machinery Wharf and Oil Wharf but Gun Mounting, Boiler, Victualling and even Bakery Wharf.

In the modern-day, the docks have survived and, if Google’s aerial photographs are anything to go by, they are kept busy.

During the Second World War, being only 60 miles from Italy, the naval facilities took a hammering. In a January 1941 raid, sixty Luftwaffe dive-bombers battered the dockyard in an attempt to sink the aircraft carrier HMS Illustrious which was alongside for repairs.

June 1940 to November 1942 is known as The Siege of Malta when the Axis powers tried to bomb and starve the island into surrender. The Grand Harbour area alone saw 3,000 bombing raids drop 6,700 tons of bombs.

According to Wiki, by April 1942 the Admiral Superintendent of Malta Dockyard reported that due to German air attacks, “Practically no workshops were in action other than those underground; all docks were damaged; electric power, light and telephones were largely out of action.”

With the defeat of Rommel at El Alamein and the Operation Torch invasion of French North Africa, Allied forces moved to the offensive and the siege ended. Due to its heroic resistance, the King awarded Malta the George Cross.

© Always Worth Saying 2022, Going Postal

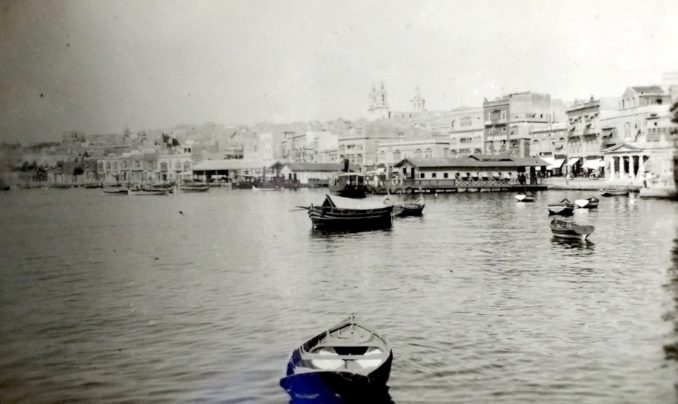

We can imagine Rob rising at an unearthly hour and walking down from Amery Street to the stages at Sliema. The spires of the Parish Church of Sacro Cour look on, as a ferry carries him to work. He dreams of the weekend when his wife, young daughter and camera will set off in the car to explore the island.

To be continued …..

© Always Worth Saying 2022