Attributed to Nicholas Hilliard, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

It is always a bonus when a book takes one or more well-known figures and makes you see them in an entirely new light. Tracy Borman has achieved just this with her dual biography of mother and daughter Elizabeth Tudor and Anne Boleyn, two of the most famous queens England has ever had.

It used to be thought that Elizabeth had wiped her mother completely from her mind, concentrating only on being her father’s daughter – a task she performed superbly well. She never sought to overturn her father’s annulment of his marriage to Anne, nor to have Anne’s body retrieved from the Tower of London chapel (where it was rumoured she had been buried in an old arrow chest) and given a more fitting memorial, and frequently referred to her ‘dear father’s memory. So it would be easy to see why this interpretation would gain precedence, especially as Boleyn had been such a divisive figure with the general masses in life. But Borman shows how, although Elizabeth knew she had to tread carefully in this matter in order to avoid creating public controversy, the Tudor queen did in fact subtly pay homage to her mother and thereby honour her memory for the rest of her life.

Ann Longmore-Etheridge, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

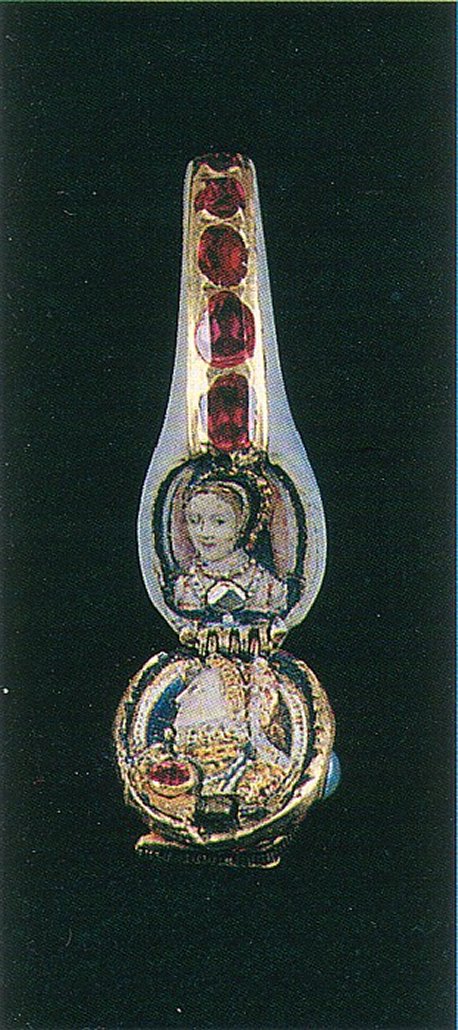

The evidence presented rests on two main categories: objects and people. Among the possessions are the marvellous Chequers locket ring, a mother of pearl ring encrusted with gold, rubies and diamonds which spell out ‘ER’. Elizabeth is said to have been wearing this ring at her death. Many historians now believe one of the two enamelled portraits inside this piece is of Anne Boleyn, although others think it could portray Catherine Parr (Elizabeth’s stepmother). The other is unmistakably a portrait of Elizabeth herself. When the ring is closed, the two faces almost kiss each other. What is fascinating, too, is that Anne here is portrayed with light reddish gold hair, unlike her standard depiction of being a brunette. Of course, no contemporary paintings of her survive (only later works), so anything to do with her appearance is mainly supposition. Some think the appearance of fair hair on the Chequers depiction could be due to the enamel wearing off, exposing the underlying metal. The ring has a phoenix on the bezel, topped by a crown. The phoenix is a symbol of resurrection, and was associated with Anne Boleyn not least in a contemporary poem, the idea being that she had died but been reborn in her daughter. To complicate the picture, other Tudor families used the phoenix as their symbol as well, including the powerful Seymours. According to legend, there can be only one phoenix at a time and when that phoenix dies in flames, a new one is regenerated. The symbol also suggested purity and sacrifice, ideas which Elizabeth would have appreciated in reference both to herself and her mother.

Other objects covered in the discussion include Elizabeth’s keeping of the ‘bed of estate’ in which Anne Boleyn gave birth to her, her selection of a set of tapestries based on a work by Christine de Pizan, an author Anne had been very impressed by when a lady in waiting at the French court, and her wearing of Anne’s jewels. She also treasured her mother’s autographed Book of Hours (a type of prayer book) and a gold cup made for Anne decorated with her famous falcon crest. This falcon motif was subsequently taken up by Elizabeth and used extensively elsewhere in her palaces and possessions.

In terms of the people, Elizabeth favoured and surrounded herself as much as possible with her Boleyn relatives including the Careys (the children of Anne’s sister Mary). However much trouble close Boleyn relations caused her, she often gave them as much rope as she could – even when they (treasonably) deliberately flouted her wishes as in the case of Lettice Knollys, who secretly married her favourite, Robert Dudley. On a progress to Norfolk, she did not visit Blickling Hall where Anne was most likely born, but did however insist on a seat in Norwich cathedral which faced the Boleyn chapel featuring Boleyn coats of arms and was in full sight of her Boleyn great grandmother’s grave. In this way, a perfectly proper public occasion could also be used for an underlying private obeisance. When Elizabeth died, Boleyn relatives were by her bedside and, as Borman notes, ‘the Boleyn coat of arms was proudly displayed throughout her funeral procession. Anne’s falcon badge was added to her daughter’s magnificent tomb in Westminster Abbey.’

Of course, Elizabeth was only two years and eight months old when a Calais swordsman severed her mother’s head on Tower Green that May morning, so her personal memories of Anne must have been hazy at best. But she seems to have managed in a private way to have continued paying respect to her mother, to what remained of her mother’s family, and to the ideals Anne Boleyn wished her to be brought up by. Some historians such as Professor David Loades have even referred to Queen Elizabeth as ‘the third Boleyn girl’.

© The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence.

The sign of a good book is that it stays with you long after you read it. With this one, I found myself looking at portraits etc of this particular queen in a totally new way. It was quite a thrill when I noticed an oval silver Phoenix medal assigned to 1574 in the British Museum collection which has the queen’s monogram on the reverse. The E and the R (standing for Elizabeth Regina) have been joined in such a way that an A and a B appear between them. This does not appear in the book, but, in my opinion, totally bears out the author’s theory.

© foxoles 2025