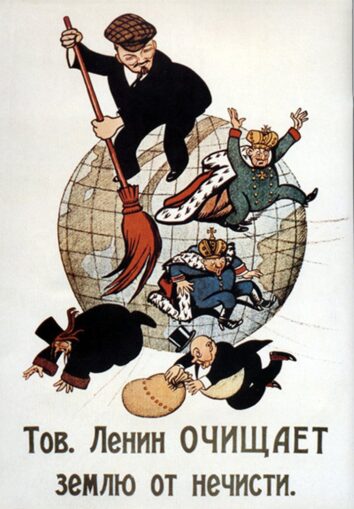

Viktor Deni, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Following Labour’s landslide victory in 1945, the government set about nationalising industry with all the fervour of true believers in the socialist cause. Coal, railways and road transport, steel, healthcare and energy utilities were all nationalised, and together with sweeping welfare reforms, by 1950, the process was largely complete. Meanwhile, post-war Germany and Japan rebuilt through mixed economies that empowered private enterprise within frameworks of strategic state intervention, regulatory reform, and coordinated planning.

By 1951, Attlee’s government had run out of money and run out of ideas. Housing demand was still and issue and rationing for some foodstuffs was still in force. The reforms of the immediate post-war years had led to high taxes and continuing austerity. As always with a Labour government, devaluation was inevitable, with the pound dropping from $4.00 to $2.80 in 1949.

Following Churchill’s election in 1951 on a promise of fiscal discipline, the remainder of the 1950s saw recovery and economic growth. This was driven in part by increasing access to credit, with HP and instalment plans becoming common for big ticket items such as cars and furniture and consumer electronics. Although the government attempted to control the increase in consumer credit in order to limit inflation and manage the balance of payments, consumers and retailers had other ideas. The rise of the retailers offering their own credit plans, alternative finance companies providing non-bank credit and mail order catalogues offering instalment plans meant that government control did little to dampen consumer demand.

Throughout this period, there was never any suggestion of re-privatising all those industries that had been nationalised over the preceding half-a-century (apart from the steel industry which was re-privatised in 1953 and re-nationalised in 1967)1. Despite deteriorating public services, a chronic lack of investment and ever-worsening industrial relations, the post-war consensus of a ‘mixed economy’ was still widely accepted by successive Labour and Tory governments.

Rolls-Royce failed in 1971, having overstretched itself developing the fan blades for the RB211 engine. Unable to raise capital on the financial markets, the company collapsed into receivership. Rather than explore private sector and private/public partnership options, the Heath government’s first and only instinct was to nationalise the company. The Heath government also partially nationalised the Upper Clyde Shipbuilders due to industrial unrest. In 1975, under a Labour government, British Leyland was nationalised.

Up to 1979, the direction of travel was clear. Nationalisation was seen by successive Labour and Tory governments as the answer to underinvestment, to industrial unrest and to the financial failures of strategically important companies.

By 1979, the country was on its knees with the winter of discontent leading to a change of government. The coming of the Thatcher era also brought with it an ideological commitment to free markets and privatisation was the order of the day. But this renewed confidence in the power of free markets was not matched with corresponding reforms to the welfare state. In fact, during the shakeout of inefficient British industry, welfare supported millions who lost their jobs.

Although theoretically committed to privatisation and with the contentious privatisation of the railways in 1996, the Major government continued to spend liberally. In 1992, the government introduced the Private Finance Initiative (PFI) which was heralded as a new way to fund public sector projects but with efficient private sector innovation and discipline. In reality, it was nothing of the sort: it was an accounting sleight of hand to defer costs and thus massage the public finances to keep within the agreed rules of the EU’s Maastricht Treaty. Over the medium to long term, PFI meant increased costs for British taxpayers.

In order to win power again after 18 years of Tory rule, Tony Blair revised the Labour Party’s Clause IV by removing the reference to the common ownership of the means of production. Many saw this as an abandonment of a major part of socialist philosophy but in reality, it was a cynical ploy to convince voters that the Labour Party had modernised. Once in power, Blair’s Labour government reverted to type with the nationalisation of the engineered financial failure of Railtrack. In the financial crisis of 2008, we again saw how quick a Labour government was to resort to bail outs and nationalisation of banks and building societies when faced with collapse. The Labour government rebadged PFI as PPP (Public-Private Partnerships) and continued to throw both taxpayers’ and borrowed money at extortionately expensive projects and schemes. Poorly managed and companies which are reliant on PPP contracts run a high risk of failure, as we saw with the collapse of Carillion in early 2018. Despite this, many services and projects are outsourced by the government and, like a car buyer seduced with a personal lease plan, it is all but impossible to extricate ourselves from the quick fix of expensive PPP schemes.

During the Tory years of government from 2010 to 2024, there were continual accusations from Labour of ‘creeping privatisation’ of public services but the reality was that the private sector was just being used for delivery of publicly funded services. This had the effect of enriching shareholders while failing to address the fundamental overreach and cost of government. When it came to the failures of train operating companies, the Tories were again quick to nationalise them. The only major privatisation during the Tory years was of Royal Mail which was largely to bring about the liberalisation of postal services required under EU rules.

And so it continues, Starmer’s Labour government is committed to greater public involvement in our lives with a de facto nationalisation of the rail network under a new organisational called Great British Railways. We have yet to see a commitment to further nationalisations but it is likely that the water industry is a target, especially if there is a financial failure.

Over the last 80 years since the end of the second world war, every Labour government has taken us up at least another notch on the socialist ratchet, each notch marked by nationalisation, regulation and increased cost to the taxpayer. Apart from the Thatcher era, every Tory government has simply accepted the socialist settlements of their Labour predecessors. Today, we have failing public services provided by a mishmash of public and private sector organisations which cost billions yet underdeliver. The national debt is £2.7 trillion (96% of GDP) and the burden of taxation is at its highest level since the 1940s. With so much public service delivery outsourced, we have unaccountable, fragmented and unresponsive organisations where value for taxpayers’ money has been sacrificed for short-term fixes and long-term pain.

Socialism has catastrophically failed us and no government has had the courage to do anything about it.

1 The private telephone companies had been nationalised in 1912. GPO Telephones did not include the Hull telephone network because it was already in public hands, being established by Hull Corporation (the city council) in 1904.

© Paul_Southampton 2025