Introduction

In my essay ‘From Socialism to Welfarism: the Betrayal of the Working Class’, I observed that the early socialist thinkers developed their ideas at the peak of the industrial revolution. Socialist theory was therefore based on the assumption that the economy was, and would remain, dominated by the extractive and manufacturing industries. I also suggested that the working class had been betrayed by socialism, its promise of prosperity for all ultimately led to a welfare-dependent class instead.

In this essay, I present a deeper analysis and critique of the journey from the socialist experiment of nationalisation in the late 1940s to the economic liberalisation of the Thatcher era. I argue that these pivotal changes in the economy of Britain perpetuated a reliance on welfare.

Twentieth century deindustrialisation

Britain’s manufacturing base continued to grow into the twentieth century and by 1948, manufacturing accounted for 48% of the economy. This had fallen to 13% by the middle of the 2010s. Although declining as a percentage of the economy, manufacturing output has steadily risen due to technological change and improvements in productivity. However, this has meant that the number of those employed in the extractive (primary) and manufacturing (secondary) sectors had declined to just below 20% by 2016.

In our post-industrial economy, the socialist idea that ‘surplus value’ of a product belongs to the workers is moot when the number of industrial workers is a very low percentage of the total.

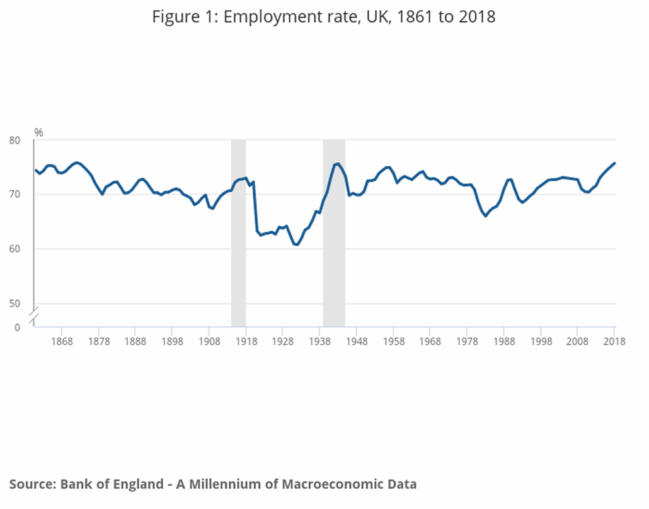

Figure 1: Long-term trends in UK employment: 1861 to 2018 – Office for National Statistics

Pivotal changes in the twentieth century economy

There were two significant changes in the British economy in the twentieth century. The first was wholesale nationalisation of industry at the end of the 1940s following the election of Attlee’s Labour government in 1945. The second was the dismantling of that nationalisation following the election of Thatcher’s government in 1979.

Attlee’s programme of nationalisation was part of an ideologically motivated drive towards greater investment in industry to bring about greater efficiency and modernisation to what was perceived to have been underinvestment and the poor working conditions of privately owned business. However, industrial growth in Britain during the following decades does not compare favourably with industrial growth in West Germany and Japan, the two countries which lost the second world war. Both countries benefitted from generous grants and loans from the USA with which they could rebuild their economies.

See: Economic Growth Germany Compared to Britain

Figure 2: Decoding the Economic Miracles: Post WW2 Germany and Japan – Economists in Transition

See: Growth in Real Per Capita GDP in Japan, Britain, and the US, 1870-2008

Figure 3: Decoding the Economic Miracles: Post WW2 Germany and Japan – Economists in Transition

It should also be noted that there was a post-war political consensus on nationalisation of industry: the Conservative governments of Churchill, Eden, Macmillan, Home and Heath did not once attempt a reversal. In fact, Heath went as far as nationalising Rolls-Royce in 1971 to save it from the imminent threat of bankruptcy.

By the middle of the 1960s and at the peak of industrial employment, the failures of nationalised industries were all too apparent. For example, steam locomotion was still in use on the railways to the end of the 1960s, the last steam locomotive being completed in 1960. So much for Attlee’s promise of modernisation. This lack of investment was repeated across industry, leading to poor productivity and poor economic growth. As always, the promises of improved standards of living from socialism failed to materialise leading to persistent industrial unrest.

Even following nationalisation, the workers were not happy. Strikes were a regular feature of the immediate post-war period and continued through the following decades with a Railway strike in 1955, a Seaman’s strike in 1966 and of course, the crippling Coal Miners’ strikes of the early 1970s. It was the industrial unrest during the winter of 1978/79 (the ‘Winter of Discontent’) that was the undoing of Callaghan’s Labour government.

Another significant factor affecting the economy during the 1960s and 1970s was the persistently high level of inflation, eroding the value of money and creating an environment where pay increases were not matched by increases in productivity. By the end of the 1970s, Britain’s political and economic consensus was no longer tenable.

See United Kingdom Historical Inflation Rates

Figure 4: UK Historical Inflation Rates | 1956-2025

The Thatcherite Revolution

It was imperative that the Thatcher government delivered results, and quickly: inflation under control, an end to industrial strife and an improvement in living standards. She was a proponent of free market economics and set out to break the post-war consensus around nationalised industries. Her programme of privatisation was met by considerable hostility, even from her own side. In a speech to the Tory Reform Group in November 1985, former Conservative prime minister Harold Macmillan characterised it as ‘selling off the family silver’:

“First of all the Georgian silver goes, and then all that nice furniture that used to be in the saloon. Then the Canalettos go.”

Thatcher had correctly diagnosed the problem. Nationalisation and the associated labour relations laws had led to a sclerotic, under-invested, low productivity economy plagued by high inflation and industrial unrest. Privatisation, even of natural monopolies, was seen by Thatcher and her allies as a universal remedy. It promised to cure inflation, restore productivity, and break entrenched labour conflict.

Thatcher was not just taking aim at the workers and working practices of the time, she also had the managers of those industries in her sights. She saw the management of the time as weak, lazy and entitled; and incapable of delivering value to long-suffering taxpayers.

What followed was nothing short of a revolution with revitalised industries bringing new investment into industry, increases in productivity, economic and the rate of inflation reduced from its 1970s highs. However, it came at huge social cost. Unemployment rose significantly during the early 1980s and regions which had been reliant on industry became reliant on welfare instead. Revenues from North Sea oil which began flowing from the 1970s were used to support the welfare bill during this period. Thatcher saw unemployment as being a necessary evil in order to defeat inflation and sclerosis. She also believed that reliance on welfare was allowing too many to take advantage and avoid work. Thus began a period when the relative generosity of benefits was reduced.

Thatcher’s unshakeable faith in the magic of free markets led her to believe that the innate entrepreneurial spirit of those who lost their livelihoods would unleash a new era of economic growth and renewal. How the unemployed were supposed to learn new skills or launch new businesses without support was anyone’s guess. Perhaps somewhat unfairly, Thatcher was then caricatured by those on the left as a heartless individualist who had no concern for the working class.

The Thatcher government also deregulated the financial services sector in 1986, with the programme of reforms known as the ‘Big Bang’. This had the effect of expanding the service sector in London and the South East of England at a time when the industrial heartlands of the Midlands and the North of England were suffering from the impact of deindustrialisation.

This asymmetric recovery, known as the ‘North-South Divide’, delivered very different economic outcomes in different regions. Looking at aggregate national economic data does not give the full picture of regional variations in productivity on the one hand and social deprivation on the other.

Wrong Remedy

Thatcherism is generally considered to have been economically successful, so much so that the Labour Party adapted Clause IV of its constitution, seen by many as an acknowledgement that even the socialists were aligned with the new economic consensus. Although the Thatcherite revolution ushered in a new age of low inflation, increased growth and higher private sector productivity, today’s economy is still feeling the negative effects of those radical reforms. Levels of unemployment in some areas are still persistently high with significant levels of reliance on benefits and there remains a disparity in wealth between London and the South East compared with the Midlands, the North of England and the former mining communities of South Wales.

Privatisation has also not been a widespread success. Although initially capturing the public’s imagination, many saw it simply as an opportunity to make a fast buck rather than seeing individual share-ownership as an opportunity to build long-term wealth. The performance of many privatised companies has been chequered, again beset by under-investment, the rapacious greed of private equity investors and the woeful lack of oversight from regulators. Notable examples are Thames Water which is on the verge of bankruptcy1; the Train Operating Companies with appalling records of service2; and the National Grid which has under-invested in infrastructure leading to hazardous equipment which regularly catches fire with catastrophic consequences3.

Conclusion

The 80 years since the end of the second world war have seen remarkable changes in the economy. The socialist experiment with nationalisation failed miserably, with complacent management, and industrial unrest due to the ongoing economic turmoil characterised by rampant inflation and currency debasement. The socialist mantra is always “it will work next time, comrade” and yet the idealism of socialist theory can never translate into workable solutions in practice.

Following her election in 1979, Thatcher’s policies addressed urgent economic dysfunction in the aftermath of the crises of the 1970s but her free-market remedies induced long-term socio-economic fragmentation.

We have also seen extractive and heavy industries dying, with no coal mines left, shipbuilding limited to a handful of key players at scale and British Steel is at a crossroads with disputed ownership and competitive pressures from abroad.

In recent decades, policy missteps have accelerated decline: Net Zero targets have further strained the industrial base and mass immigration has placed an unsustainable burden on the welfare state.

It is easy to be critical of the governments of the time because they were faced with extraordinary economic difficulties which meant having to take decisions which, although well-intentioned, subsequently proved to deliver far less than hoped. We also have to be mindful of that politicians live and die by the electoral cycle, they have to deliver in shorter time-frames than robust and long-term economic renewal allows.

As noted in ‘From Socialism to Welfarism: the Betrayal of the Working Class’, a significant part of Britain’s population is now welfare-dependent with an entrenched bureaucratic class which is an ever-expanding burden on the public finances. Growth is illusory and funded by monetary expansion rather than production.

Where do we go from here?

Footnote 1: Thames Water Crisis: Sewage, Fines and Flood Risks | Unda

Footnote 2: Passenger rail performance | ORR Data Portal

Footnote 3: National Grid skips crucial upgrades as mystery blazes sweep network (Paywall)

© Paul_Southampton 2025