The American Civil Liberties Union has been a primary litigant in challenging President Trump’s position that the offspring of illegal immigrants into the United States do not acquire US citizenship. ACLU Immigrants’ Rights Project Deputy Director Cody Wofsy said the organization is going to keep working until [President Trump’s] order is defeated completely across the country. This is the official position Wofsy has taken on behalf of the WCLU:

This is in the Constitution, and this was taken out of our president’s hands in 1868, so we can have all the debates that we want. But the law is clear,” he said. “This is unconstitutional and illegal.”

Anthony D. Romero, the executive director of the ACLU, has stated his position:

Birthright citizenship is the principle that every baby born in the United States is a U.S. citizen. The Constitution’s 14th Amendment guarantees the citizenship of all children born in the United States (with the extremely narrow exception of children of foreign diplomats) regardless of race, color, or ancestry.

Wofsy and Romero are referring to the passage of the Amendment XIV to the Constitution, ratified in 1868. Section 1 states:

All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the state wherein they reside.

First, we should understand the cloud under which the 14th Amendment lies as described by Wikipedia:

The amendment was bitterly contested, particularly by the states of the defeated Confederacy, which were required to ratify it in order to regain representation in Congress.

Where in the Constitution is Romero’s exception to Amendment XIV about the children born to foreign diplomats? It doesn’t exist. Romero has spun that exception out of thin air.

To determine the intent of Amendment XIV we need to look first at the wording of the amendment and then at the law that preceded it to determine if Amendment XIV reversed the prior constitutional law, or merely identified a specific exception to the prior law.

When we parse the language of Section 1 of the Amendment XIV, we come across this phrase indicating the exception:

… and subject to the jurisdiction thereof …

That does not translate into,

All persons born or naturalized in the United States, excluding foreign diplomats, are citizens of the United States and of the state wherein they reside.

Clearly there were more exceptions that were intended, so we should look at the meaning of jurisdiction to determine their extent. Does it mean the individual is expected to adhere to the laws of the United States (federal law) and the law of the states, does it mean payment of certain taxes, or is there a more fundamental requirement to determine what jurisdiction means? This is where it is necessary to understand the law that was in place just prior to Amendment XIV. The law that applied to citizenship is called the law of nations, which is referenced in Article I, Section 8 of the Constitution:

To define and punish piracies and felonies committed on the high seas, and offenses against the law of nations;

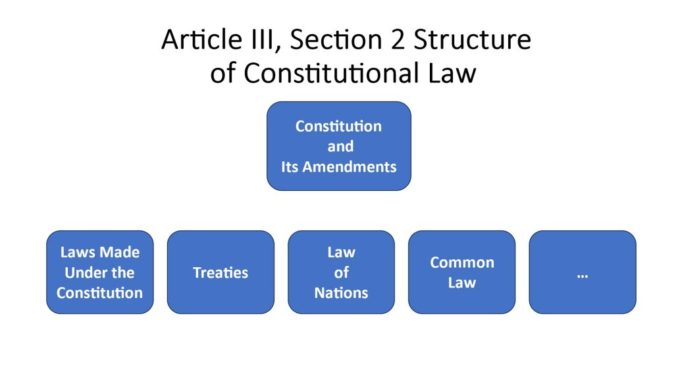

At first blush we might reject the law of nations for citizenship definition because this reference is only about piracies and felonies committed on the high seas. That would be a mistake. United States law is the combination of the Constitution, which is recognized as the supreme sub-system of law, and other sub-systems of law, including treaties and the common law. The former are specified in Article III, Section 2:

The judicial power shall extend to all cases, in law and equity, arising under this Constitution, the laws of the United States, and treaties made, or which shall be made, under their authority; …

Treaties are mentioned as a part of the system of law in the original Constitution of the United States, but not the common law. Common law was not referenced until Amendment VII was ratified on December 15, 1791, two years after the formation of the federal government. That amendment states:

In suits at common law, where the value in controversy shall exceed twenty dollars, the right of trial by jury shall be preserved, and no fact tried by a jury, shall be otherwise reexamined in any court of the United States, than according to the rules of the common law.

Clearly the common law was implicitly recognized between the forming of a federal government in 1789 and the ratification of Amendment VII in 1791. Amendment VII made explicit what had been implicit previously, that there were other sub-systems of law that are incorporated into the overall system of law of the United States. They are subordinate to the Constitution, and when there is a conflict between the Constitution and its referenced sub-systems of law, the Constitution prevails.

The Clear Intent of the Constitution’s Amendment XIV

Once we have a view of the structure of law in the United States, we need to focus our attention on what Amendment XIV clearly states:

All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof [emphasis added], are citizens of the United States and of the state wherein they reside.

The law of nations (Vattel, The Law of Nations, P. 219) is specific about the granting of citizenship – it is derived from the parent’s citizenship (the law of nations states that the father is responsible for the civic education of offspring, but consensus today would insist that both the mother and the father are responsible). The law of nations insists that a citizen ultimately must be parented by citizens, not foreigners. That understanding prevailed from 1789 until 1868 when Amendment XIV was ratified. The framers of Amendment XIV certainly were aware of the conflict between the law of nations definition and the modern idea that the common law prevailed allowing the offspring of non-citizens to automatically become citizens because they were born on soil considered to be United States territory at the time. Amendment XIV was written the way it was because the framers of that amendment saw no conflict. They did not intend that anybody would become a citizen who did not meet both requirements:

All persons born or naturalized in the United States, AND

Subject to the jurisdiction thereof

We can argue about what it means to be subject to the jurisdiction of the United States, but it is clear that illegal immigrants declare themselves outside of the jurisdiction of the United States by violating its immigration laws.

Even if we dismiss that argument and assume that either the law of nations or the common law might apply to the children of illegal immigrants, the law of nations should prevail because an international standard for the granting of citizenship is essential to the concept of international law. The law of nations standard addresses which nation is deserving of the loyalty of the citizen. The law of nations points to the possibility that Nation A and Nation B might go to war, and both nations insist that the individual serve in their military. The law of nations was created to resolve that conflict. The European Union and other governmental entities may choose to grant dual citizenship, but that conflict does not go away. The law of nations still applies because it addresses the conflict between the two citizenship definitions.

Summary

The law of nations continues to apply to the awarding of citizenship today in the United States. Amendment XIV was designed to address a specific fault in United States law, that slaves were denied citizenship because they were previously viewed as property. Amendment XIV corrected that fault, but it was never intended to allow the offspring of illegal immigrants to become citizens. If it were, the amendment would need to be as explicit as the 21st Amendment XXI was in nullifying Amendment XVIII (prohibition of alcohol). The law of nations still applies to citizenship.

© Phil Duffy 2025