Busy times for Mrs Francis Killen. The adverts had been placed. The VIPs were on their way. The early weeks of 1960 saw her guests begin to converge on Merseyside. If her curly-wired bakelite GPO phone were to ring, it would likely be a call from a film star. In an infrequent appearance in the city bearing his name, Lord Russel of Liverpool was a ‘certain’. He would travel up with the bachelor Earl of Lanesborough, the chairman of Mrs Killen’s association. Their founder Captain Laikhoff was pencilled in but as a distinguished absentee.

A resident of Reading, the Captain wanted to attend but had been very ill in hospital with doctors refusing permission for him to journey north. He promised to visit in the late spring. Another Captain, A H Finney, their northwest organiser, was a definite. He would be accompanied by his wife Kim and their guide dog. For the association in question was the Guide Dogs For The Blind, whose first training establishment had been founded in nearby Wallasey. Mrs Killens’ local association was the new but heartily active Liverpool and district branch and the forthcoming event was a variety show fundraiser. Actors Terry Thomas and Robert Morley promised to compare a midnight entertainment featuring an all-star programme.

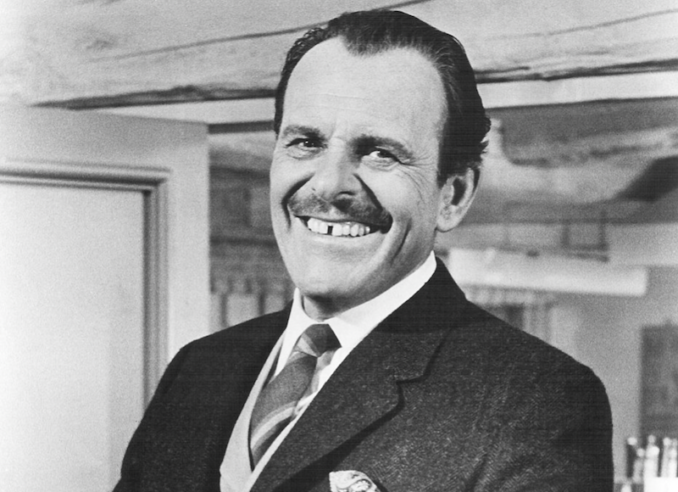

The phone rang. It was Terry Thomas. Mrs Killen was no doubt excited to hear the irrepressible gap-toothed actor – at the time one of Britain’s best-loved comedians – tell of one or two big surprises for the audience among the guest artists. Perhaps tapping his nose at the other end of the line as he spoke, the star of ‘How Do You View?’, BBC TV’s first-ever comedy show, was bound not to say any more or give any clues. Little did Mr Thomas and the artists involved realise it was themselves who were in for a surprise.

English actor Terry-Thomas in May 1951,

LLC NYC – Public domain

A newspaper advert from Thursday 11th February 1960 put flesh on the proceedings. They would take place in the Odeon Cinema on London Road, round the corner from Liverpool Lime Street station. At midnight on Friday 26th February, The Guide Dogs For The Blind Association invited readers to meet Terry Thomas in person as he introduced Robert Morley, Patricia Bredin, Lorree Desmond, Sally Barnes, The Littlewood Songsters and a host of other artists.

Seats were 5/-, 10/6, 1gn and 2gn with all proceeds going to the above charity. The Odeon box office would be open from 10 am – 8 pm and on Sundays from 4 pm – 8 pm. Late transport would be available.

A great success, the all-star midnight show attracted an audience of 1,200 laughing and clapping their way into the early hours. It was hoped the event had raised about £2,000. Besides the advertised acts, the surprise acts were Dennis Kirkland, Jaqueline Farrell, Moira Moon and Devlin and Irene. Besides The Littlewoods Songsters, music was also provided by Ralph Reader and members of his Gang Show. However, an ambitious young local comedian was missing from the line-up.

Despite the seriousness of subsequent events, page five of the following Sunday’s Weekly Dispatch reported in the upper-class cad-style of the characters often played by Terry Thomas,

‘I say, chaps, what an absolute shower! Someone’s stolen Terry Thomas’s cigarette holder. The holder, as famous as the gap in the comedian’s front teeth, was taken by a sneak thief who raided the dressing rooms during a midnight variety show at Liverpool’s Odeon theatre yesterday. Terry Thomas made the discovery after the show which he had compared with a cigar in his mouth instead of the cigarette holder. He values it at £2,000.’

Thomas returned to his room to find the black bamboo cigarette holder containing 42 diamonds missing. Two singers were also robbed. Patricia Bredin lost a fountain pen and nine pounds in one-pound notes from her handbag. Four pounds in ones were gone from the possessions of Lorrae Desmond.

Liverpool CID men were called to the theatre and spent some time examining the rooms and making enquiries. The officers established Terry Thomas went on stage at 01:15 am leaving his trademark gimmick diamond-studded cigarette holder in his dressing room. When he returned at 3:20 am it was gone. Given the publicity surrounding the theft and the uniqueness of the goods, it is unsurprising that disposing of the gems proved difficult.

Unemployed salesman and sometime variety artiste Alan Williams was seen on March 11th by detectives Exley and Hammond in Whitechapel, Liverpool. Told it was believed he had some diamonds, the twenty-eight-year-old of Stockville Road in Liverpool’s Mossley Hill replied, ‘I’ve only got two.’ He then brought out from his pocket a jewel box containing two diamonds and, suggesting he knew them to be stolen, said, ‘A man asked them to sell them for him.’

He was taken to the police station for further questioning. In no coincidence, later the same day a twenty-year-old aspiring comedian called James Joseph Tarbuck was sought by the police and found in Liverpool’s Queens Drive. When challenged by officers Tarbuck said, ‘You can search me, I have nothing.’ When further quizzed about stolen diamonds and no doubt realising what the police might already have been told, Tarbuck commented, ‘You seem to know all about it. It was me who took Terry Thomas’s cigarette holder.’

The detectives went with Tarbuck to his family home in Queens Drive where hidden in rolled-up carpeting about the hallway, they discovered 40 diamonds and pieces of gold setting – the remains of Terry Thomas’s holder broken up to be disposed of. Tarbuck told the police he had gone to the Odeon to try to get on the show. He was disgusted at not getting a part and as he was leaving noticed the star’s dressing room door open. He took the cigarette holder from a table and after keeping it for a week, broke it up and sold two diamonds for £3 because he was in debt. He then gave Williams two diamonds to sell for him. Of the other performers easy-to-dispose-of missing cash and fountain pen, there was no mention.

Liverpool Odeon, England,

Jay Galvin – Licence CC BY-SA 2.0

Detective Chief Inspector J W Bonner presented the pair and the evidence against them to a magistrate who remanded them on bail. Tarbuck was charged with stealing the cigarette holder, Williams was charged with being an accessory. The full trial began on April 29th before recorder Judge Laski. Terry Thomas himself gave evidence in connection to the disappearance of his £2,000 gem-studded trademark.

Introduced under his full real name, Thomas Terry Hoar-Stevens, the celebrity told Liverpool Crown Court the said holder was made for him to his design by a Birmingham firm and was insured for £2,000. However, when quizzed about how much he paid for the item, Thomas claimed ignorance but said it could have been £1,500. At a pre-trial hearing it had been suggested the £2,000 value was a publicity stunt. Terry Thomas had replied, ‘How can you say such a thing? Of course, it is not. If it had been a publicity stunt surely it would have been easier to have it made from gilt and glass?’

Back in the full trial and in a further twist, Mr David McNeill acting for Tarbuck handed Judge Laski a document (not read out in court) which the defence council said gave a more realistic valuation of the stolen goods. In response, R S Trotter, prosecuting, conceded although the cigarette holder was insured for £2,000 it was likely worth less. In mitigation, McNeill repeated to the court that Tarbuck expected a part in the show but was not called. His action was in the nature of pique rather than of dishonest intent. Of further benefit to the defendants, Inspector John Parry said both of the accused came of good families. In conclusion, James Joseph Tarbuck having pleaded guilty was put on probation for two years. Alan Williams was given a conditional discharge for 12 months.

***

Over six decades later it would be churlish to wonder why Thomas – an extravagant spender, notorious with money and who died in poverty in a nursing home – would go on stage holding an unfamiliar cigar while his over-insured trademark lay in an unguarded dressing room. In the middle of the night. In Liverpool. But it has to be said that in early 1960, Terry Thomas was facing difficult, risky and expensive transitions in both his personal and professional lives.

As the austere fifties turned into the swinging sixties, cinemas were showing ‘Blue Murder at St Trinians’ where Thomas co-starred with George Cole and Alistair Sim, and ‘I’m All Right Jack’ featuring Thomas as Major Hitchcock in a star cast including Ian Carmicheal and the legendary Peter Sellers. However, Thomas’s were supporting roles. Also in early January, Thomas starred in what he claimed would be his final TV play, aptly entitled ‘Lord Arthur Savile’s Crime.’

For, in a syndicated article published the same month, he expressed his dissatisfaction with variety and television and announced plans for a career in (risky) cinema complimented by the occasional selected theatre role. The Port Glasgow Express reported this as an important milestone for the entertainer who had found fame from the gap in his teeth and regularly caused millions to switch on their TV screens and sit back confident of a good laugh and a satisfying night’s entertainment.

Promotional still of Terry-Thomas,

Employee of United Artists – Public domain

Thomas began his film career as a pre-war extra alongside other extras such as Michael Wilding and Stewart Grainger who were to become big-screen household names. ‘I’ve been in love with films ever since. I adore the atmosphere, the entertainment, the silences,’ Thomas told the Express, adding in character, ‘And I adore the tea. My, oh my, that tea! Yes, I love the tea. I don’t intend to forsake the theatre as I owe a lot to that, of course. But I am now looking for a suitable play. You can be seen, in fact, far too much on the small screen, and I’ve had my fill of it now. Radio or TV variety – never again. It’s the cinema for me and me for the cinema. It’s the greatest medium of them all.’

Post-war, Thomas starred in films including ‘Too Many Crooks’, a black comedy about a botched robbery starring Sid James and Bernard Bresslaw. Interestingly, his Pinewood Studios schedule for 1960 included ‘Make Mine Mink’ alongside Hattie Jaques and Billie Whitelaw. Terry’s role was as a retired Army major who leads an upper-class gang of boarding-house guests who steal mink coats and sell them – albeit for charity.

Away from his professional life and only weeks before the Liverpool performance, Thomas initiated divorce proceedings against his wife, the interesting South African dancer and choreographer Ida Florence Patlansky, who went by the stage name Pat Palanski and was also known as Ida Thomas and Ida Hoar-Stevens. The couple became involved while part of a short-lived cabaret double act, Terri and Patlanksi, and married at Marylebone registry office on 3rd February 1938.

Later in 1960, Thomas called off the divorce. The couple having parted in 1957, Thomas’s council Stanislaus Sueffert had been claiming desertion but had given up, ironically because Ida couldn’t be found. Mr Sueffert told the newspapers, ‘I don’t know where she is, I have been trying to contact her. She was in the South of France the last time I heard from her.’ Terry Thomas added, ‘I didn’t even know that. I don’t know where she is now. This withdrawal has really nothing to do with me. It is a legal thing. And it definitely does not mean there will be a reconciliation.’ Asked if the divorce would proceed along different lines he replied, ‘I don’t know. It is all in the hands of my lawyers.’

As a further sign of true love run cold, Mr Colin Duncan defending for Mrs Thomas, informed Judge Mr Justice Stevenson his client had no interest in the proceedings other than that her husband should pay her legal costs. Judge Stevenson obliged and in doing so added further to Terry Thomas’s financial troubles. In early 1962 the couple did another 15 rounds with this time Terry being sued for divorce by his wife. Thomas offered no defence to Ida Florence Hoar-Stevens of Boxhill Road, Wadsworth, Surrey’s petition on the ground of desertion, albeit from 1954, three years rprevious to her ex-husband’s recollection.

***

As for the other party to the events of January 1960, the patriarch of that good family was bookmaker Joseph Tarbuck, whose turf accountant’s premises sat further along the same street as the Odeon at 170a London Road. The family home on Queens Drive was a substantial bay-windowed semi-detached property on a main thoroughfare in the respectable Walton area of the city, nestled between the open spaces of Stanley and Walton Hall parks.

© Google Street View 2024, Google.com

The young Jimmy Tarbuck attended Dovedale Primary where he was in the same class as John Lennon, a year above newsreader Peter Sissons and two years above another Beatle, George Harrison. After completing his education at Morrison Secondary Modern and while still an 18-year-old, Tarbuck hit the headlines in 1958 after coming first in the comedy section of the Pwllheli holiday camp final of the People newspaper’s National Talent Contest being held at all Butlins holiday camps and hotels.

In the People write-up, Jimmy is described as a hairdresser and as a comic with a kick, as three footballers teamed up with him to write his ‘patter’. Jimmy Melia, Bobby Campbell and Johnny Morrisey were the young Liverpool FC players hoping to put Jimmy in with a chance of a share of £5,000 prize money. Tarbuck himself had been a trialist at Liverpool FC and played in the Welsh League.

The following September Tarbuck, by now the compare of the ‘Oh, Boy’ stage show, married Pauline Carfott at Our Lady of Mount Carmel R.C. Church in Toxteth. Halfback Bobby Campbell performed as best man. But the honeymoon proved a short one. A three-month tour with Marty Wild, Wee Willie Harris and the Bachelors interupted and saw Jimmy appearing as a bottom-of-the-bill comedian (only out-ranking the talking dog and unicyclist) at the likes of the Huddersfield Ritz and the Sunderland Empire. Early the next year, London called with the touring artists supporting Cliff Richard and The Drifters at the Granada, Tooting.

With a career pause because of the court case, the old newspaper cuttings remained untroubled until 1963, albeit for the parochial world of Manchester clubland. As a Mike Hughes entertainment talent, Jimmy performed at the Ashton-under-Lyne Oxford Club and the Carlisle Club in Eccles. By the autumn, his big break approached. The Liverpool Echo reported, somewhat disingenuously, Tarbuck had reached the Palladium after only eight months in show business. Out of hundreds of acts across the North, he’d succeeded in an audition for ABC Television’s ‘Comedy Bandbox’. Filmed in advance, London impresario Val Parnell took in the programme at a private showing and was so impressed by Tarbuck he booked him to appear on his ratings-topping show ‘Sunday Night at the London Palladium.’

The rest, as they say, is history. With his mop-hair, quick wit, smart suit and cheeky chappy stage bonhomie, Tarbuck rode the sixties zeitgeist – alongside contemporaries such as the Beatles and Cilla Black – as the Merseybeat comic. Following the Liverpool Echo timeline, the long-time resident of the exclusive gated Coombe estate near Surrey’s Kingston upon Thames now celebrates his 60th anniversary in show business. Interviewed recently on morning television he told a revealing tale from his school days. A teacher asked of classmate John Lennon, ‘If you had two half-crowns in one pocket and a shilling and three pennies in the other, what would you have?’

‘Tarbuck’s trousers on,’ came the impish and knowing reply.

© Always Worth Saying 2024