When I lived in London in the early 2000s, I explored all the surrounding counties by bike. Of them, Essex was perhaps the most interesting. It suffers from more negative stereotyping than any other county (except perhaps God’s Own) because of its cockneyfied Thames-side belt and its accent. But the central and northern parts of Essex are as quietly beautiful as anywhere in southern England. Parts are remote. And its North Sea coast, famous, or rather notorious, for Clacton and Jaywick, is actually full of surprises. This piece is about two of them.

Hands up those who are not locals but have heard of the Dengie Peninsula. Not many, I see .. This odd tongue of Home Counties farmland lies north of the Southend conurbation, part of a patchwork of flat, empty peninsulas and islets forming the eastern fringe of the county. At its southern tip, where the Crouch runs into the sea, is Foulness.

The seven-by-five mile island at the Thames mouth has been a military area for two centuries and was then being run down by the MOD’s chemical warfare organisation Defence Evaluation and Research Agency (DERA). I had always assumed it was off-limits.

Pedalling across Dengie at this time, however, I was told by a villager that you could visit, that people actually lived out there among the bunkers and barbed wire and whatnot. It was the “land that time forgot.” (Later, I found just about everybody calls it that.) Across the water, it looked flat, featureless and boringly estuarial. As unalluring an island as I had seen in a while. Had to be worth a trip.

The fun started with the process of getting there. Your first step then — it looks a bit more organized today — was phoning up the landlord of the pub, the George and Dragon. The island was still mostly off-limits, but there are two hamlets on it, Churchend and Courtsend, and the pub acted as a kind of gateway to both. You had to make a phone appointment with landlord, Fred. So I called. Come along, said Fred. A weekday afternoon was agreed. That was it. It seemed a quintessentially English approach to granting clearance for a maximum-security chemical weapons facility.

This train-and-bike journey began with the 10.44 from Limehouse in London’s East End to the end of the line at Shoeburyness, via Basildon. Shoeburyness looked odd — a combination of railway depot and seaside resort at the end of the Southend riviera. Cycling along the last, short lane to the island, I met an old man sitting on a bollard after his morning constitutional.

“Eighty-five I am, and still getting about on me pins,” he replied to my greeting. We nattered, and I enjoyed hearing the old Essex accent, a variant of East Anglian, which has all but vanished now.

He then told me he had spent 20 years on Foulness with the army. My ears pricked up. He was surely old enough to be beyond caring much about the Official Secrets Act, but still alert enough to remember stuff. Worth a try … What exactly did they do there? Ah, hard to say, nobody knew what the other sections were up to. What had he done? A chuckle. “Explosives, and such like, that’s what they did out there.” But he wouldn’t be drawn. I waved goodbye and rode on to the water’s edge.

The island is really only a slightly detached piece in the jigsaw-like Essex coast. Even with a height of a few dozen feet, the bridge leading onto it is a landmark.

“Now, you say Fred’s expecting you?” said the guard at the security building. He called Fred. Fred cleared me. I couldn’t see the point of this arrangement.

“Got a camera?”

“Yes.”

“Well, don’t use it. And stay on the road, don’t go anywhere but the pub, and come straight back. Alright? Have a nice trip.”

I don’t quite know what I was expecting, but Foulness was far from being the land that time forgot. The straight road across the island had a thin but steady traffic of cars, tractors and military vehicles — there was even a bus service — and the tower blocks of Southend and tankers queuing up to enter the Thames were constant reminders of modernity on both horizons. It looked simply odd.

The shoreline was littered with old trains — “let’s say they’re for storage,” the cagey security man had said — and the farmland was dotted with shot-up concrete ruins and crisscrossed by security fencing. Here and there red flags fluttered, but they were not shooting that day. Only the pretty white weatherboarding of the older cottages and the wading birds in the creeks softened the overall bleakness. The hamlets, and the island’s uniqueness as a wildlife habitat, saved it from conversion into London’s third airport in the 1970s. But, truth to tell, it would have made the perfect site.

The weatherboarded George and Dragon, dating from 1659, stood in the middle of Churchend, the central hamlet. I found both hamlet and pub empty.

“Get more in at the weekends,” Fred said. “They call us the land that time forgot.”

“Otherwise it’s local trade?”

“And workers. They’re scaling things down here now, using outside contractors.”

The islanders, his wife said, had passes and could come and go at will. A few commuted to Southend. None, it seemed, took their lunch at their local. Worse, I had picked closing day at the pub’s local history room. With even the neighbouring church off-limits, there was nothing for it but to make Fred’s steak pie last as long as possible. But Fred wasn’t feeling chatty, and I ate in silence. Then all I could do was pedal back.

I didn’t discover much on Foulness, but the county histories have a fair bit to say about it. Although the island was long notorious for its bad airs, the name refers to wild fowl, such as Brent Geese and avocets, to which it was a better home than to men. Like many English wetlands, it was made more habitable by Dutch drainage engineers in the seventeenth century, but it remained a rough-edged resort of smugglers, horse-thieves and runaways. Bare-knuckle fights were held outside the George and Dragon, which acted as dressing room, venue and refreshment area all in one, and one local champion, John Bennewith, was the son of a landlord. Even one of the vicars occasionally decked unruly members of his congregation.

Until the 1920s, the only access was by ferry or by using the Broomway, an offshore causeway following Maplin sands nearly the length of the island. Thought to be a Roman road laid on what was then dry land, it is exposed at low tide and was always a risky passage. In the floods of 1953, it again provided the only access.

The military moved in during Napoleonic times. Because the tide recedes over 20 kilometres, further than anywhere else in Europe, weapons developers could test-launch their latest projectiles into the sea and retrieve them later from the mud. It was on Foulness that Henry Shrapnel tested a long-range shell that fragmented above the enemy, showering them with shot. It took twenty years to win over the military authorities, but this revolutionary weapon, which made long-distance artillery truly effective for the first time, played an important part in defeating the French. The more familiar meaning of shrapnel evolved later.

You can still visit Foulness. I had intended to update the details of access, but it is all online, and I expect there will be somebody who doesn’t read the comments who can add local knowledge below.

* * *

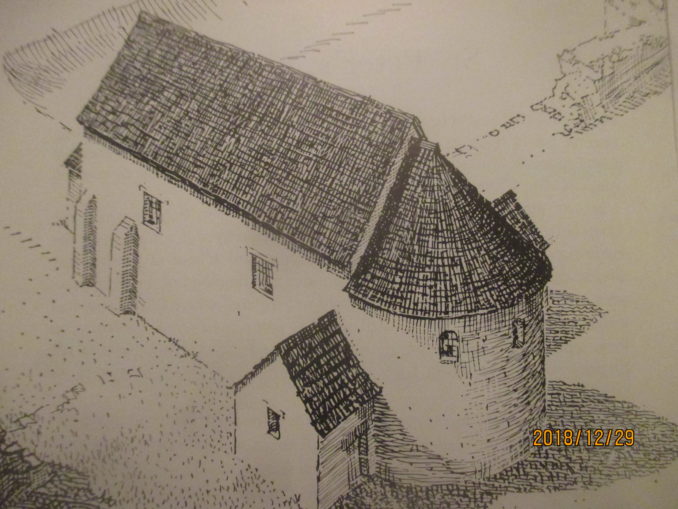

Barely a dozen miles north as the crow flies, but forty or fifty by road as you have to leave one peninsula and travel the length of another, is the chapel of St. Peter-on-the-Wall near the village of Bradwell-on-Sea. If the George and Dragon is remarkable for where it is, St. Peter’s is for what it is — a still functioning Saxon place of worship. It is not quite unique, says the guidebook, but I have never seen any Saxon building so intact — only the window glass and tiled roof are obviously modern — nor any Saxon site that so vividly evokes the Saxon age.

It has survived because it is stone, a material the Saxons seldom used. They were not imaginative or skillful builders, and the nicest thing you can say about the church as architecture is that it has the simple, sturdy appeal of a Dales barn. Its siting is also striking. St. Peter’s stands quite alone at the remote northern tip of the Dengie Peninsula, over a mile beyond the village it serves, on the flat, bleak North Sea shore — the Saxon shore. It is an odd place for a church, and the reason is that it was built on, and in fact with, the still-visible ruins of the Roman fort of Othona, which was served by a good road heading inland. Like Hadrian’s Wall, St. Peter’s provides a direct physical link with the ancients.

St. Peter’s is a long, long story that can only be outlined here in the broadest of strokes. The fort, Othona, is thought to be one of a chain along the Saxon shore (coastal Kent and Essex) raised during the slow disintegration of the Roman Empire, the Broomway at Foulness probably being part of the same works. Its builder was probably Carausius, a Romanized Gaul — a Belgian in modern terms — and naval commander who succeeded in briefly severing Britain and parts of Gaul from the empire and governing them as a private dominion until his assassination in 293. (He is best known to numismatists, for he sought to publicise and legitimise his rule by issuing lots of high-quality coinage with his name.) The fort, which can be traced in outline on the ground, was probably intended to defend the Saxon shore primarily against the dispossessed Romans.

St. Peter’s was built by St. Cedd three and a half centuries later, in 654, a time when, as the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles tell us, Welsh-speaking people were still being driven out of England. It is tempting to imagine the saint’s weary party hauling their boat onto the beach here after the long voyage over the North Sea and laying the first stone in thanks at their safe arrival in the new land of the East Saxons, choosing the site of the ruined fort deliberately to portray themselves as successors to the Romans.

Although he was a Saxon and did arrive by boat, St. Cedd was in fact a monk of the Celtic church, and was sent down the east coast from the monastery established by an acolyte of St. Columba at Lindisfarne. Serving as the base from which the East Saxons were Christianised, St. Peter’s became a monastic foundation, and St. Cedd was made Bishop of London. Hence the little church was the first cathedral in Essex, and possibly in England.

St. Cedd died of the plague in 664 at a religious foundation in the North York Moors, now the village of Lastingham, and his end was shared by 29 members of a party of 30 who came up from Bradwell for his funeral. He was struck down just after the Synod of Whitby, where he had agreed to the abandonment of his own Celtic church for the Roman as the national church.

Somehow, St. Peter’s survived the Vikings — perhaps they kept it as a landmark, as church towers were sometimes spared in World War II. In time, a new church was built at Bradwell, and St Peter’s became a chapel-of-ease. In the seventeenth century, it seems to have fallen into disuse, and was eventually converted into a barn. It was only re-consecrated in 1920. Now in regular use, it attracts annual pilgrimages.

I was lucky enough to arrive late on a breezy, clear Sunday in summer, just in time for Evensong. Because the building has only tiny windows and slits, they had left the door open to allow more light in. I stood there, listening to the singing from the dark huddle inside mingled with the lapping of the sea, alternately watching the altar candles flicker in the draught and, outside, the sea birds rolling on the breeze and the long grass waving. Apart from the Victorian hymn, this could have been the year of the church’s foundation, 1,300 years previously. The emotion was racial rather than religious. Whatever the history books say, at that moment it did seem a shrine to the Anglo-Saxon settlers, erected where they first waded ashore.

The illusion vanished the moment I turned away from the church and sea and began the long trek back to the village, for there was no overlooking Bradwell’s other eye-catcher, its nuclear power station.

Foulness Foulness Island, Essex’s best kept secret

St. Peter’s. Train to Southminster, bus to Bradwell, walk the rest of the way

© Joe Slater 2019 2024

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file