I was delighted so many readers have enjoyed my recent accounts of sailing in the north of Scotland and thank DJM for writing – “A life well lived”. I couldn’t ask for a better epitaph but hope he won’t mind if I just keep it in a drawer somewhere for the time being. I stopped sailing when I was 79 and realise I’m getting on a bit now – but I haven’t yet quite reached the stage of “Pushing up the Daisies”.

The very first article in this series answers Cynic’s question about why I took up this lifestyle and I suggest he (or she) reads it if looking for a painfully truthful answer.

My response to the second question is that many working seamen do regard leisure sailors as dilettantes. In quite a few developed countries skippers of fishing vessels in particular show resentment at what they regard as intrusion into the domain from which they make their living. According to maritime law they do have right of way but not of exclusive use. Some are more agressive than others in asserting it. The law also stipulates sail has prior right of way over power, but try telling that to an oil tanker bearing down on you! I am reminded of the story of one VHF conversation by a newly qualified yachtsman who tried to insist on his rights in such a situation but got the reply – “ME BIG SHIP, you little ship, GET OUT OF MY WAY”.

Mountaineering and sailing for pleasure is not exclusively European or American but it’s probably true the Europeans first started both sports.

Mont Aiguille near Grenoble was climbed in 1492, the same year that Columbus sailed to the Americas. Admittedly that might not be classed as a climb for pleasure as Antoine de Ville apparently made the ascent on the orders of French King Charles VIII to demonstrate the techniques being developed for storming castle walls at the end of a siege.

Wikipedia reckons the modern era of climbing for pleasure really got going in the 19th century as a spin-off from shepherding in high and rocky places. Wealthy people were developing the activity into a challenging sport by the 1880s more or less independently in England’s Lake District, Germany’s Saxony region and in the Italian Dolomites.

One of the earliest ascents of this era was that of Napes Needle on Great Gable by WP Haskett Smith in 1886. I did the same 70 years later and by the same route too, also used by the climbers in this photo-

Sailing as a sport similarly grew in Holland from the early development of small fast craft to chase Pirates, into ones used to meet incoming trading vessels when the first to bring back news of the arrival and its cargo gained a commercial advantage. I alluded to early sailing for sport in Part 9 of these articles when mentioning how descendants of Charles II’s Court developed it by forming the The Royal Cork Yacht Club as a result of his pleasure in the activity during his 10 year exile in Holland.

Here’s a copy of the painting of “Mary”, the first “Royal Yacht”, arriving at Gravesend in 1689 bringing to England the daughter of James II, of “William and Mary” fame. Incidentally, that was 18 years before the formation of the United Kingdom to rescue Scotland from bankruptcy caused by the latter’s failed attempt to set up a colony in Darien – now the province of Panama adjacent to Colombia.

My conclusion from all this is that both Mountaineering and Sailing are now long established sports that originated from ordinary workaday life in Europe.

I can also confirm Stop It’s comment that sailing for pleasure is now enjoyed world-wide by many ordinary people from many nations. In addition to meeting sailors from the US and all EU countries I can name, I remember a solo Black South African in the Caribbean, a number of Ukrainians on the small atoll of Suvarov in the middle of the Pacific, a solo sailor from Japan in Fiji, a couple in Indonesia from land-locked Switzerland and Australian, Canadian, white South African and New Zealand yachtsmen and women in many other countries. The very similar motivation and experience of such amateurs created a club-like atmosphere not dissimilar to the one I detect amongst most of the Puffins here. I write of course about the atmosphere in the first fifteen years or so of the 21st century. It may be different now, especially in this era of the semi-professionals who finance their expeditions by creating videos of them.

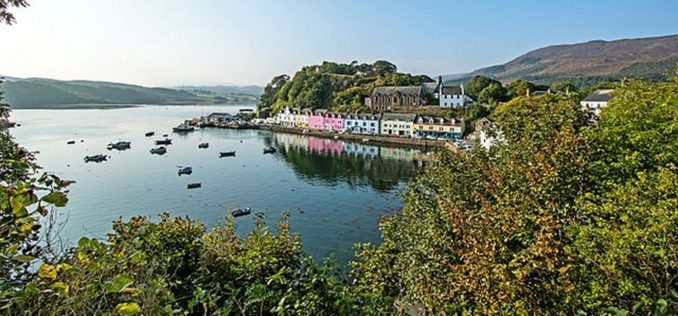

ALCHEMI’S 1997 VOYAGE – IN PORTREE HARBOUR

Returning from distant times and places to the end of August in 1997 I am reminded of the strange feeling of being alone on the boat in Portree harbour with lots of clearing up and cleaning to do in preparation for the arrival of a new crew.

The people I was expecting were Frances, a young woman who had been on the same “Coastal Skipper” course at Sailing School with Michael and I in early 1996. She had also come with me on my second visit to the Scilly Isles in the same year after I was shown the way during Alchemi’s maiden voyage by Pacific Seacraft’s UK Agent (Part 8).

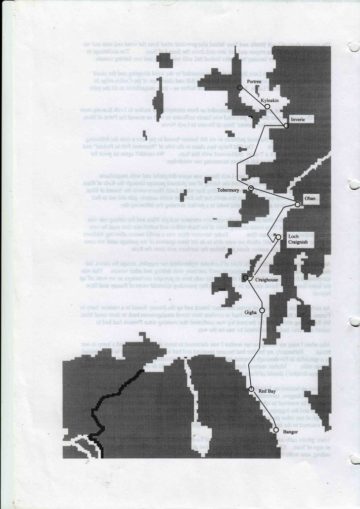

I had tried to interest two people for both the Skye to Bangor and Bangor to Falmouth legs of the 1997 voyage. That had proved difficult, perhaps because they would both be in Autumn with its shorter days, colder weather and equinoctial gales.

Nevertheless, Frances had agreed and I had met an itinerant chef in Falmouth marina who was keen. I was too, finding the idea of a sybaritic life on my own yacht with my own chef appealing – I think I imagined myself as a sort of micro-Abromov.

Sadly, that was not to be.

In those days I had an early mobile ‘phone and could access the internet by using an external modem with a DUN connection (Dial Up Network) – terribly slow of course and only possible at all when visiting a middling size or larger town that had a Network. The first news to reach me in Portree by those means was that Frances had cancelled.

Never mind I thought, two of us should still be enough to manage the yacht.

But then my hopes of an easy life with delicious food were dealt a blow when my chef didn’t arrive on the appointed day. Nor on the next. Nor did he reply to emails I somehow or other managed to send. Nor did anyone answer the ‘phone number he’d given me. On the third day I worried that if I didn’t start immediately I might not get to Bangor in time to meet John for the last leg of the voyage.

PORTREE TO INVERIE

I first sailed the boat single-handed whilst based in Swanwick the previous year, three or four months after she was delivered. My efforts then were limited to motoring in both directions along the river Hamble after sailing for a short distance in the Solent in fine weather and moderate breezes.

I expected the leg from Portree to Bangor during the first two weeks of September to be somewhat different.

I was so pleased by Whistler 80’s remark on Part 28 that he felt he was making the journey with me that I’m going to narrate events as they happened even though some might think one or two decisions were foolish. I always thought they would make a good story to tell my grandchildren if I survived and that is what I am now doing (but including Puffins amongst the readership as well).

My first challenge was to work out how to release the lines securing Alchemi to the buoy in Portree harbour. The primary load-bearing connection was through my Swedish mooring hook to avoid chafe and that would be easy to do from the deck because the hook was open-ended. But for that very reason I had asked Michael to attach a load-free secondary line to the ring on top of the buoy with a round turn and two half-hitches.

Those half-hitches had to be converted to a slip line with no knot that I could withdraw whilst standing on deck. The buoy and its own line to the seabed were too heavy to lift so I had to use the dinghy to untie the hitches at sea level.

That all worked, but I also decided to tow the dinghy as I had seen many other yachts do instead of taking the time and effort needed to lift it back on deck, deflate it and stow it safely. That all worked too.

The next challenge was to stop again at the quayside in the Kyle of Lochalsh where we had tried to refuel on the way in but had been forgotten in the press of other tasks the harbourmaster had been engaged upon. Here’s a quote from my journal –

There followed a rapid rigging of warps and fenders with the ladder as a fender board to span the pitch between piles at the quay. Soon I was sidling alongside with the centre of the boat opposite a vertical ladder up the stone wall. A very short line to a ladder rung secured the boat long enough to throw a bow and stern warp to two locals about 15 feet above me on the quay whose only comment was to enquire what had happened to my crew. The harbourmaster was full of apologies for having forgotten us a few days before and his lady assistant did the honours by driving the tanker close enough for its hose to reach Alchemi’s filler pipe in the cockpit.

Picking up a buoy in Kyleakin bay was just a matter of reversing the departure procedure and went off without a problem. I was just in time to hear the 17:50 shipping forecast and was not too perturbed by “… south-east 5 to 7, perhaps 8 later….” because the same prediction had failed to materialise the week before and anyway the Sound of Sleat is well protected from the East.

Elated by my first day of single-handing for real I prepared and enjoyed a properly cooked supper and retired early for the night with the alarm set for 06:00 to catch the period of slack water through Kyle Rhea. That all worked fine and after emerging from the narrows I was able to hoist the full main and jib for a couple of hours in a 10-15 knot south easterly breeze. During this period the dinghy pranced over the low waves like a lifeboat speeding along on a practice day.

Then –

Soon after passing the Ornsay lighthouse the wind increased to 20 knots, gusting 25 and backed towards the south depriving us of shelter from the land. Never mind I thought, a few furls on the jib and a reef in the main will look after things.

So they did to begin with but when the wind increased again to 25 knots gusting thirty I furled up the jib completely and continued under reefed main and staysail only. It was at this stage the dinghy started to imitate a glider, launching itself off the top of waves and then landing again with a giant splash. I tried a longer tow rope and then a shorter one but it didn’t seem to make much difference.

Then the blessed thing carried its aeronautics further and did a victory roll in mid air that it finished off by skimming the waves as before only this time it was upside down. I found I could right it by pulling it up close to the stern and lifting its nose until the wind caught it again and flipped it right way up.

By this time the wind generator was making a real racket and when I glanced at the wind speed display it was reading 30 knots, gusting 36. I reduced sail further by taking a second reef in the main and things settled down for a bit.

Now, the dinghy, tired of pretending to be a glider, decided to play at being a submarine instead. It had already perfected the art of taking off and landing upside down but, bored by just skipping over the waves it found it could see better below the surface if it stuck its nose into the next wave and dove downwards until the towline tightened and pulled it up again.

That of course put a great strain on the painter and its attachment point so I had to haul it up on deck, deflate it and bundle it down into the cabin as there was no time to fold it up and tie it down properly.

With no dinghy to worry about and the wind generator switched off it seemed really peaceful sailing down the sound in 30 knots plus but I was quite pleased when I came into the lea of the hills near Mallaig and picked up a buoy at “The Old Forge”

After all the excitement it was quite a relief to sit quietly at Alchemi’s chart table and write up this log. The dinghy seems none the worse for its experiences but I have reflated and refloated it ready to go ashore in the morning.

I shan’t be saving a bit of deflation and inflation work again if there is anything more than a force 4 forecast. (In later years I realised part of the problem arose because I was towing with a single line to the prow of the dinghy. A tow is much more stable if one uses a bridle with two lines joined to a float in the middle and with the ends tied off respectively on either side of both yacht and dinghy).

I was hoping for a happy ending to this part of the voyage at the time but that was delayed for a few days as I’ll now tell you in this further extract from my journal.

It is now Saturday, 6 September and I’m still here at Inverie in Knoydart.

Wednesday and Thursday passed in one continuous gale with the boat rocking on her mooring like a nodding donkey gone mad in winds between forces 7 and 9.

Despite the short fetch across across Loch Nevis it was so rough I couldn’t face the journey ashore in the dinghy and when I went forward to check the anchor chain, mooring hook and secondary line the bow was rising and falling through five or six feet. For the most part I stayed below with the hatches battened down – Norman and Michael certainly saw Scotland and its outlying islands in more favourable conditions.

On Thursday night the dinghy blew away and I cursed myself for failing to check the knots after the strain they had been under on the passage along the Sound of Sleat. Too late to worry about that as I saw each gust wash it higher up the rocks on shore, followed by each wave carrying it back into the loch again.

I knew from our inward visit that “The Old Forge” maintained a VHF watch in the evenings, but couldn’t find their channel number in the Pilot Book and they didn’t respond to calls on emergency channel 16 or channel 80 as used by most English Marinas. By trial and error I found them on Channel 12 and a member of staff kindly went out to rescue my dinghy. He called back in due course that it was undamaged and that he had secured it above the high water mark.

On Friday morning the wind had abated to force 5 or 6 and the tide was full tempting me to to make an approach alongside to recover the dinghy. However, the pier is made of unforgiving concrete and there was still a considerable swell running.

The swell had subsided by 17:00 so I made an approach only to find the depth had reduced to a level I was unhappy with. I probably would have pursued the attempt with others on board to handle the ropes whilst I manoeuvred the boat and held her in position, but it all seemed too difficult on my own so I beat a retreat to moor again on one of the two buoys nearest the shore.

Having seen several boats leaving and arriving at their moorings and the pier, and my efforts at landing having been clearly visible to them and people ashore without inducing any offers of assistance I was reluctant to call again on the VHF and ask for further help.

Perhaps the next step was foolish but my thoughts at the time went along these lines – “This is the third serious difficulty you have faced (the first was when the engine was stopped in the dark by discarded fishing net seizing the propeller in a busy shipping channel and the second when creeping round extremely shallow water without a detailed chart at the SE corner of Zeeland) If you’re going to succeed in adopting this lifestyle you have to become more self-reliant and not cry for help every time something goes wrong. There’s another obvious way to recover the dinghy”.

With some trepidation I put on the dry suit, snorkel mask and flippers. I also thought it would be a good idea to tie my longest and lightest line to an empty milk bottle and cast it from the boat as an umbilical cord on which I could pull if I got into difficulties.

Having made these preparations I clambered down Alchemi’s swim ladder and, clutching the cord set out for the shore. After what seemed like an age but was probably no more than a minute or so I stopped, and raised my head to discover I was no nearer land but had swum about thirty or forty yards from the boat parallel to the shore.

Thinking – this is ridiculous – I set out once again determined to check direction and position more frequently.

After a short distance I came to the empty milk bottle with cord fully extended and realised the idea of a safety line was really a non-starter. Having come thus far I could not admit defeat and released the cord while continuing to paddle away until my legs ached.

Looking up again soon afterward I estimated my position to be about midway between boat and land and started to wonder if this really was a good way of recovering the dinghy. Thinking I could remain just floating for a rest if need be I paddled away again until my legs ached some more.

The shore still seemed to be a long way off but suppressing momentary anxiety I doggedly paddled away and through the goggles began to see a slight change in water colour. With renewed hope I paddled away some more and was rewarded in due course with sight of weed tendrils drifting far below.

Slowly the tendrils seemed to rise in the water until I was fighting my way through them as though hacking away at creepers in a jungle, and indistinctly but still some distance below, I could see stones upon the bed of the loch.

On auto-pilot now and disregarding the aching limbs on I paddled until I felt my knees bump up against some stones and realised I had made it and could breathe normally if only I could raise my body out of the water and stand knee deep in wavelets breaking on the shore.

Now it was just a matter of regaining my breath, resting, and waddling along the shore in my webbed feet like an aldermanic penguin until I could row back to the boat.

Once aboard I felt like lying down for the rest of the evening but still had rubbish to dispose of and fresh water to obtain.

It didn’t take long to replace the secondary mooring line with chain instead of rope, pour the spare container of Fair Isle water into the tanks, row ashore to fill it again and dispose of the rubbish.

It was with considerable relief that I made my way to the “The Old Forge”, there to buy drinks for Mark, Janet and Judith who had all played a part in the dinghy rescue the previous evening.

I also found a couple of pints of “The Young Pretender” complemented my dinner of haddock and chips very well. The publican invited me to stay on the buoy without charge for as long as I liked and, equipped with an expensive T shirt to commemorate these events, I got thoroughly wet again launching the dinghy, rowing back to Alchemi, and hoisting it aboard to be tied down securely on deck.

Was it foolish at the age of 61 to be imitating James Bond at the peak of his powers? Perhaps, but I was still pleased to have solved the problem I had myself caused without needing to call on external help.

Reliving the experience as I write this article I think again of DJM’s epitaph. This was a more exciting retirement than pipe and slippers by the fireside and I wouldn’t change anything if I were transported back 24 years (except perhaps for using a towing bridle instead of a single line and checking the security of my knots more often and more thoroughly).

Throughout the few days I was confined to Loch Nevis I found solace in the music and books carried on board. Reading “Kidnapped” again and “Catriona” for the first time whilst listening to La Boheme and other favourites provided a different world in which to immerse myself whilst the weather was so dreadful.

To conclude this article I quote again from my journal –

Now, it is Saturday evening and I am still here in Loch Nevis and the forecast is still force 5 to 7 with rain. I shall listen again to the early morning forecast and decide then whether to launch Alchemi and myself on the 40 mile passage south around Ardnamurchan Point to Tobermory on Mull.

To be continued …………….

© Ancient Mariner 2021