The Shay, Halifax,

John Lord – Licence CC BY-SA 2.0

There is a shortage of lorry drivers, micro-chips and articles. Strange times that allow me permission to ramble. Put the thesaurus away. Forget about those long German words. If Shakespeare or Bernard Shaw or Oscar Wilde said something interesting it can wait. Let’s talk about football. I do have a social life away from the Puffins. Not much of a one. I don’t want one. Besides very close family and friends, little appeals. I’m not on social media. It is a corporatist sewer. Except. The windswept terraces call. Memory’s sepia eye sees an oasis shimmying in the lifeless desert that is the past. I tip my cap to only one thread of the modern age’s obsession with being electrically connected to others. My dopamine trip is “English Football in the 1970s”. A call to prayer from a long lost promised land where rivers flowed with Bovril and smelled of stale tobacco trapped beneath the roof an outsized tin shed.

I have company, some of it notable. Frank Worthington’s brothers stepped below the line to thank us for our kind words and reminiscences when the former (amongst many others) Huddersfield Town, Leicester City and England striker left this mortal field in March. Richard Dinnis sprang to the defence of his 1976/77 Newcastle United side, reminding us they finished fifth that season and qualified for Europe. Tony Currie’s son is generous with old photos, many of them never before published. “That’s my husband, we’ve been married for 52 years,” announced Mrs John Tudor below a photograph of the former Newcastle United striker.

She lingered, enjoying her own and our memories. From a native Ilkeston, there had been spells at Coventry, Sheffield United, Stoke City and Newcastle United. Stints in Belgium and America followed. Unlike today’s long-faced billionaires, Mr and Mrs Tudor had loved every second of it.

We have our fallings-out on the board but there is also consensus. Malcolm MacDonald told a cracking tale. A near half-century later he still does. Terry Hibbit could start a war in an empty room. Many who knew the late Blackpool, Liverpool and Wolverhampton Wanderers midfielder Emlyn Hughes are iffy about him.

There was something in the water in Ashton-under-Lyme. World Cup winner Geoff Hurst was born there. As was 1966 squad member Jimmy Armfield, who sits easily in our 1970s group, playing his last game for Blackpool in 1971 and not leaving the Leeds United’s mangers role until 1978. Armfield never had a bad word to say about anyone in his subsequent career as a radio commentator. He played the organ at church. Top man.

Our third Ashton-under-Lyme World Cup winner has to be squeezed into seventies football to the accompaniment of a blind eye. Born in the Tameside market town in 1977, Simone Perrotta when of AS Roma earned a winner’s medal as part of an Italy squad victorious in Germany in 2006.

Besides the aforementioned Currie and Worthington, all are agreed the number of England caps awarded to Bowles and Marsh were derisory. I would add Duncan Mckenzie to the list. As Southgate, Sancho, Saka and Rashford may testify, the leaden arm of the FA has rested across the shoulders of successive England managers while unhelpful words of obligatory advice were whispered.

Derby County 68-9,

It’s No Game – Licence CC BY-SA 2.0

Kevin Beattie of Ipswich Town and Tony Green of Albion Rovers, Blackpool and Newcastle United were two greats whose careers were cut cruelly short by injury.

There were some unlikely provincial dots on the map we all recall made for an uncomfortable parka, flares and platform shoe clad away day. This author was surprised by and at Mansfield Town’s Field Mill. The walk from Turf Moor to Burnley Central was always long on a dark November tea time.

Regardless of the welcome, Halifax’s Shay was the worst ground in the league. There was competition. Bury’s Gigg Lane had tarmac slopes rather than terracing. I arrived at the away end early to find the ground surprisingly full. There were no floodlights. Kickoff 2 pm. Chester’s Sealand Road visitor’s end was a pile of rubble. The toilets at Workington was the wall at the back of the terrace, “gentlemen” helpfully painted upon it. Although it is out of our time span and I risk moderation for saying so, a mere four years before being appointed manager of Liverpool, Bill Shankley was manager of Workington Reds. The ground did not have electricity.

In the 1970s there was no phone. Whenever the Borough Park club dallied with the back page, Doug Wetherall of the BBC and Daily Mail (whose definite pronunciation of St James Park stands to this day) had to sprint to a public call box five minutes before full-time and blag his way to the front of the queue.

Different times.

At the other end of the away day spectrum, the camber on the pitch at Burden Park, Bolton, was magnificent. At Leeds Road, Huddersfield, the Himalayan terracing disappeared into the clouds on every wet West Yorkshire Saturday.

Some unanimous decisions may surprise the uninitiated. Everton should have won the league in 1974/75. In the same season, if matches lasted 85 minutes instead of 90, Carlisle United would not have been relegated from the top flight.

The hardest man in football was Hull City’s Billy Whitehurst. Or was he? There is a debate.

At which point, bruised and aching gentleman players of Rugbys Union and League and of football American and Australian may raise a point of order. Yes, the round ball game attracts too much rolling about on the floor. Yes, the Association version is not an impact sport. Indeed, it is mainly below the waist.

England national football team arrives at Schiphol,

Bert Verhoeff (ANEFO) – Licence CC BY-SA 1.0

But there are various parts of the lower body that aren’t supposed to stretch or twist too far from the normal. It does hurt. Next time you have to stop a charging 18 stone Afrikaner, instead of using your arm and shoulder, put your leg across his body while keeping the other foot firmly planted on the ground. See what I mean?

Ah, the hardest man in 1970s football. As befits a former bare-knuckle boxer, Whitehurst’s victory is a split decision. Anyone who can defecate in a yoghurt pot and order an apprentice to take it back to the supermarket and demand a refund because ‘it tastes of shit’ demands some kind of recognition. But others snap about his ankles, looking for his hard man’s Achilles heel.

Firstly, he only just creeps into the seventies, playing in the non-league for Retford Town, Bridlington Trinity and Mexborough at the end of the decade and not signing to the Elysian fields of Hull City’s Boothferry Park until 1980. However, a pedantic friend informs me a decade begins with the year that ends in 1.

Secondly, there is always a big shout for Edinburgh born Dave MacKay who played for Hearts before being part of the legendary Tottenham side that won the double in 1961.

If you can recall MacKay dominating opponents for five hundred first division games across the 1970s, you’d be as wrong as I was before the record book intervened. Memory’s sepia eye. Dave MacKay retired from playing in 1972 after a season with Swindon Town. He didn’t play in the top flight at all during the seventies, having helped second division side Derby County to promotion the previous season before his move to the Wiltshire club.

Here’s something else that might catch you out. Who was the manager of the Derby side that won the First Division Championship in 1975? No, it wasn’t Brian Clough. At the time, he was walking along the River Trent to Nottingham. Take another bow, Dave MacKay.

As for the Scottish internationalist’s presence on the field of play, I can remember a well-known newspaper photograph from White Hart Lane. The famous old Shelf is in the background. In the middle distance stand a young Terry Venables and a concerned referee. In the foreground, an irate lantern-jawed 6’4” MacKay is pictured in profile picking Billy Bremner off the ground by the neck of his jersey. Not quite, reference to the photo shows the then Tottenham and Leeds players eye to eye. Mackay was only 5’8″ but solidly built. In his Rothmans’s entry, he was just over twelve stone, making him overweight under the modern day’s obsession with bodies, their masses and an index.

As for the other 1970s hard men with their names in the frame, Whitehurst was a six-footer but Liverpool’s Tommy Smith, of whom his manager Billy Shankley noted was “quarried not born” stood at 5’10”. Chelsea’s Ron ‘Chopper’ Harris was 5’8”, Nobby Stiles, 5’7”.

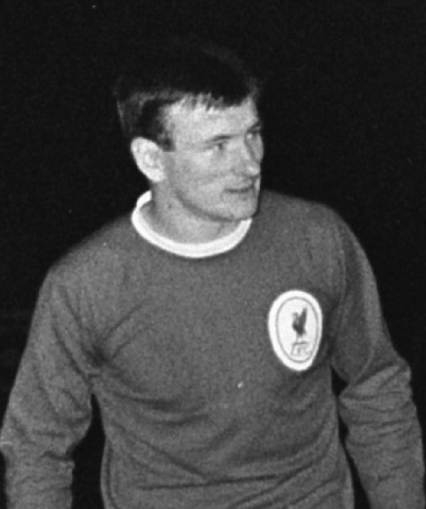

Tommy Smith in 1966,

Eric Koch / Anefo – Licence CC BY-SA 2.0

They say a good big ‘un is always going to be better than a good little ‘un. I’m not so sure and neither are the other members of the Fullback’s Union. An eclectic look though some of my favourites shows Mick Mills and John Gorman both at 5’7”. Partnering Mills in that Ipswich side was 5’10” George Burley.

If the land of square goalposts and numbers on the shorts may be allowed to intervene, Danny McGrain was also 5’10”. On the dark side of Glasgow, John Greig tipped the tape measure at 5’9”. Further afield Marco Tardelli of Juventus and Italy, of whom Jimmy Greaves (5’8”) once quipped was responsible for more scar tissue than the surgeons at Harefield Hospital, was also a few inches shy of six foot.

Our first rule of being one of football’s hard men is that you don’t have to be a giant. Indeed, being so makes the centre of gravity higher during the tackle and puts a bending strain on those longer limbs that need not concern a shorter, stockier gentleman athlete.

Neither do you have to be a brawler. In fact, it spoils the image somewhat. In a famous televised pitch punch up from Derby County’s Baseball Ground, Francis Lee’s (5’8”) combination of haymakers and jabs makes him look like the little bloke in the pub who had his pint spilt. Opponent Norman Hunter lands on his bum outwith a blow connecting. It is embarrassing. No, football’s real hard men have iron self-control. You lose your temper, you lose the argument. Red cards are for your team’s expendable fancy dans found at the nose bleed side of the halfway line.

Proof? When Boca Juniors and Argentine international Alberto Gonzalez slapped Bobby Moore in the face during a towsy 1966 World Cup match, the England captain just laughed at him. I rest my case.

Therefore, under our Gonzalez rule, we shall disqualify the bad-tempered. Billy Bremer, Alan Ball, Alberto Tarrantinni, there are others, you all know who they are.

Off the pitch, our hard man will be self-effacing, embarrassed by the tough guy moniker. More disqualifications.

The pendulum swings further towards MacKay who was embarrassed by the Bremner photograph and winched every time he was asked to autograph it. The Baseball Ground being long vacated, a statue commemorates him at Pride Park stadium. Instead of a plinth, it sits in half relief against the main stand beside the player’s entrance. In the modern style of such things, it looks nothing like him but he does appear, appropriately, to be running through a brick wall. Gets my vote.

Although Dave MacKay passed away in 2006, Billy Whitehurst is still with us and was last heard of working in the stores at Drax Power Station. It’s your turn to tell him he’s not the hardest man in football. When you do, pray a suspiciously full pot of yoghurt is not within reach.

Dave Mackay Memorial, Derby County FC,

David Dixon – Licence CC BY-SA 2.0

© Always Worth Saying 2021

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file