Billy Wilder was born in Austria in 1906 , but became a screenwriter in the late 1920s when living in Berlin. Appalled & concerned about the rise of the Nazi Party, he moved to Paris in 1933 and there directed a couple of forgettable films, but moved to the U.S. shortly after that. He was later quoted as saying of this period “the optimists died in the gas chambers; the pessimists have pools in Beverly Hills”.

As Billy Wilder drove around Hollywood in the 1940s, he was fascinated by the great mansions behind the high gates and hedges along Sunset Boulevard. Mostly built in the 1920s by movie folk with more money than sense, they were garish structures, showy and ornate, incongruously gothic but now showing clear signs of disrepair. In some of them lived silent stars of the screen whose careers had been scuppered by the arrival of sound. There they still were, superannuated and forgotten: what did they do with themselves, Wilder idly wondered? And so the germ of a story was born.

Sunset Boulevard, is possibly the best film made by Wilder, ahead of such iconic masterpieces as Double Indemnity, The Lost Weekend, Some Like it Hot, The Apartment & Ace in the Hole. Part Hollywood tragedy, part neo-gothic noir, and perhaps the best film Hollywood ever made about itself. It’s only real rival for that title is Singin’ in the Rain, but Wilder’s vision was darker, more acerbic, almost vicious in its cynicism. The writing is heartbreaking, sardonically witty, darkly funny & packed full of Hollywood inside jokes. With its break-neck pacing, expert narration & incredible cast, you have a film that can still hold its own, more than 70 years after its first release. At the time, it went down like a ton of bricks with the film industry moguls, one of whom, Louis B Mayer, berated Wilder after a preview screening for Hollywood’s elite. “You have disgraced the industry that made and fed you!”, Mayer reportedly roared. “You should be tarred and feathered and run out of Hollywood!” But Wilder, who may have felt he was only telling it like it is, calmly replied: “Go f*** yourself”.

What was everyone so upset about? Their fury centred around the character of former silent star Norma Desmond, (Swanson) a grotesque and deluded shrew who cannot bear to face the truth that the world has forgotten her. Corrupted by fame, devastated by its removal, she in turn corrupts a young screenwriter called Joe Gillis (Holden) by making him her gigolo. Once a place charged with optimism and invention, Hollywood had become populated in the main by needy youngsters like Gillis and his friend Betty Schaefer,(Olsen) hovering hopefully in the wings and waiting for a chance that would probably never come. And for all cinema’s possibilities as a new medium, most Hollywood movies were like soap powder – market-tested anodyne products. They were bereft of any new ideas or artistic merit. No wonder Mayer and others were furious but, as ever, the perceptive and far-sighted Wilder had got it exactly right. For in 1950, old Hollywood was tottering on its foundations: television was about to blow a hole in its monopoly, and the iniquitous studio system would shortly collapse. And good riddance, Wilder seemed to be saying, if the best it could do was churn out pap and treat stars like Norma Desmond like disposable livestock.

After the film’s release, the producer Charles Brackett would insist they had always intended Gloria Swanson to play the role of Norma, but that’s not entirely true. Wilder approached silent stars Pola Negri and Mary Pickford, contacted Mae West, and even persuaded Greta Garbo to meet him to discuss the film. She listened politely, and said no: unlike Norma, Garbo had walked away from Hollywood in order to preserve her sanity, and she was not about to relinquish it now. Swanson had walked away too, moving to New York in the 1940s to forge a new career in theatre and radio. It was George Cukor who suggested Swanson to Wilder: she was not thrilled about being asked to do a screen test for a film made by a studio (Paramount) she had helped create, but quickly realised this was not the sort of role you turned down. Though she had avoided unhappy obscurity herself, Swanson was uniquely placed to understand how Norma Desmond might feel about having been “put on the long finger” by Hollywood. She brought operatic levels of despair and madness to the role, but also pathos, playing a demented ageing version of herself.

Montgomery Clift was cast to play the doomed screenwriter Joe Gillis, but withdrew before filming started, citing similarities with The Heiress, a film in which he had just starred. Clift was involved with a much older woman, the singer Libby Holman, and may have been worried about adverse publicity. He would in any case have over-acted (as usual). Wilder needed a calmer, quieter actor as a counterpoint to Norma’s histrionics. He chose William Holden, a young Paramount player whose career was on hold, going nowhere. He was a hard drinker, and a complex man, but Wilder got on well with him, and they would become future regular collaborators. Switching effortlessly from cynical to sympathetic with natural ease, Holden caught Joe Gillis’s overcompensating swagger brilliantly.

When we first meet Joe, he’s floating face-down in a swimming pool. He’s dead (Jim) but not as we know it. His voice tells us how he got there. It’s a stunning opening, and typical Wilder, whose films were always led by bold, original writing.

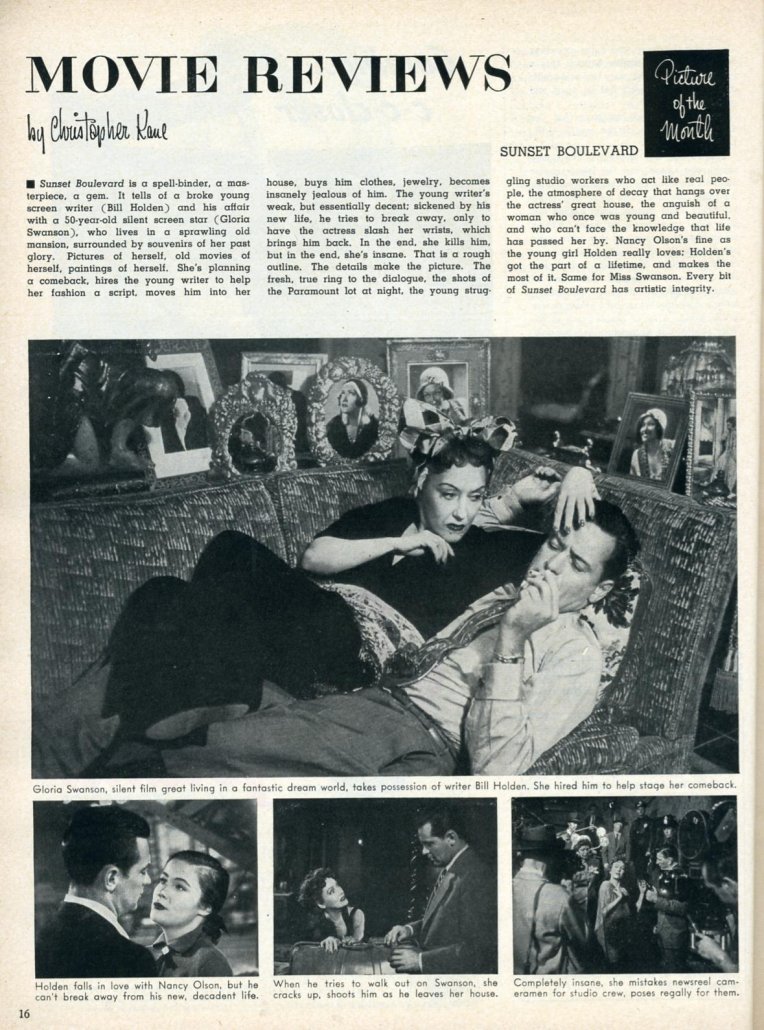

Joe’s troubles had started when he pulled into the driveway of a rundown Sunset Boulevard mansion, attempting to hide from repossession men who want to take back his car. He’s hiding when he hears a woman’s voice calling, and walks towards it. A frosty butler called Max (Erich von Stroheim) ushers him into the presence of Norma Desmond, whom he instantly recognises. She is about to bury her pet monkey and assumed he was the animal undertaker: this should alert Joe to the madness that lies ahead; he ought to run, instead he stays. When Norma finds out he is a writer, she asks him to edit a script she has written for a new film, Salomé. It will be her comeback. Joe ends up moving into the mansion, edging ever closer to an uncomfortable relationship of convenience, in which “romance” is traded for fancy suits & a living wage. As his self-loathing grows, Joe is offered a chance at redemption by Schaefer, a fresh-faced young writer who is clearly in love with him. But Norma has woven a web too dense for Joe to escape.

Sunset Boulevard is full of extraordinary scenes and moments, like Norma’s lavish New Year’s Eve party which no one attends, or the ghastly mix-up where she ends up driving to Paramount Studios to meet Cecil B DeMille, imagining he has been trying to contact her. Then there are “the waxworks” as Joe calls them, the small group of former stars who gather chez Desmond for a weekly bridge game. One of them is Buster Keaton: this, then, was how Hollywood treated its legends. And those truly unforgettable lines. “You used to be in silent pictures,” Joe says when he meets her. “You used to be big.” “I am big,” Norma ripostes indignantly, “it’s the pictures that got small.” Her butler (Stroheim) writes the fan letters she receives himself, & ritually screens for “Madame” one of her forgotten films, as Norma coos over her lovingly revisited close-ups. “We didn’t need dialogue. We had faces.” Norma’s madness is revealed in all its deluded glory as she walks down her staircase towards what she believes are movie cameras (they’re actually newsreel hacks covering a crime) and mutters those immortal words: “All right, Mr DeMille, I’m ready for my close-up”.

The story is a morality tale, a tragedy told as a joke, and over the years people have tended to focus more on the humour – it is there in spades – but there was an underlying sadness behind it all. As a budding screenwriter in 1920s Berlin, Billy Wilder had admired the scale and sheer chutzpah of Hollywood films, and marvelled at the unalloyed glamour of its stars. What was behind it all? Nothing but greed, cynical marketing, the bad taste of the nouveau riche, and variously unhappy lives. Hollywood had turned out to be a tinny illusion, a parody of itself. Wilder’s epic is a gripping, isolating, thrilling & tragic noir, an absolute must watch for any film fan.

And if you, noble Puffin, have ever dreamed of Hollywood fame, beware of what you wish for. Some get the swimming pool, some end up face down in one.

That’s entertainment…

© DJM 2020

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file