It was after the third accident in the pony trap going down Pitsford Hill that my wife said to me, ‘We really ought to buy a motor car. After all, this is 1910 and we have to move with the times.’ She thumped the plaster cast encasing her broken arm on the table to add emphasis to her words.

It had not been the fault of our coachman James. The pony Barack was a skittish beast and tended to bolt when he sensed the vehicle bearing down on him as he descended the steep slope, no matter how firmly we applied the drag brake. But there was no doubt that my wife was right.

Living in a village in the heart of rural Somerset, we would not find it easy to transform ourselves into motorists. James, however, was full of enthusiasm for all things new, and told us that there was a course available in Taunton for aspiring drivers and mechanics. We enrolled him on it at once, to his great delight.

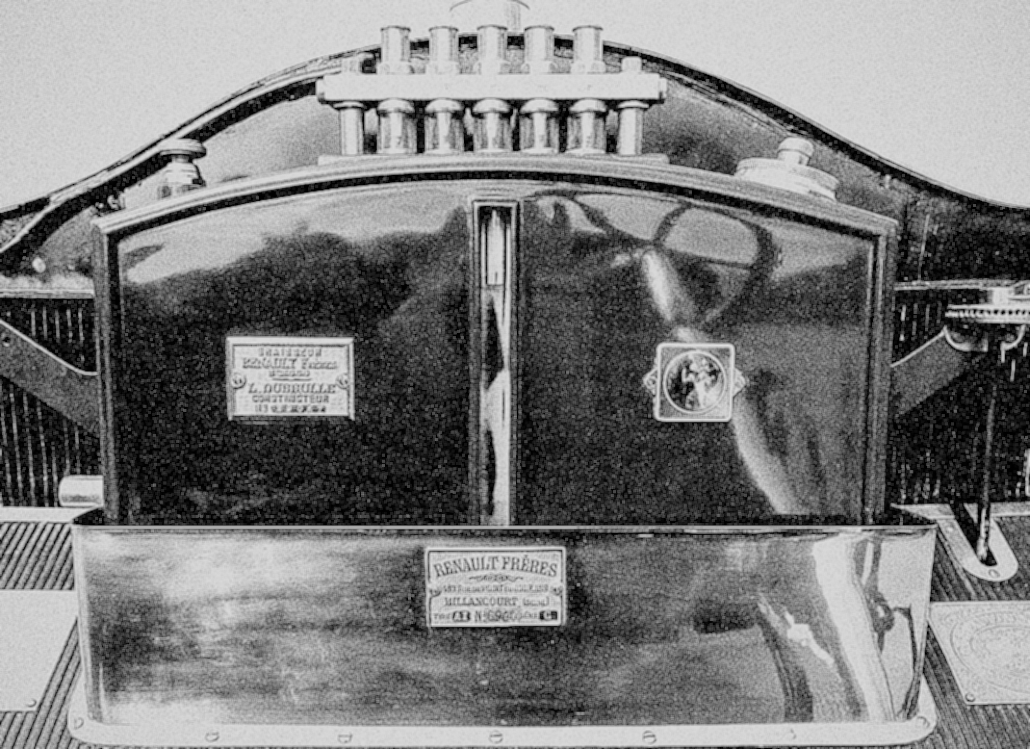

When he returned six weeks later proudly clutching his certificate, we discussed the purchase of a suitable machine for the family. We could not afford a Rolls-Royce, as the better equipped models were already priced at more than £1000, but neither did we wish to saddle ourselves with a cheap and flimsy runabout such as the Austin 7 horsepower which could be had for a mere £150. On James’s advice we decided on a French machine, a Renault Type AI Sport CT – medium sized, solidly built, powerful and with a good reputation for reliability. The model we chose, with a landau body built by Renault Frères themselves, cost 450 guineas with our chosen options which included a handsomely fitted interior.

The car was delivered to Taunton station two months later, and when it had been unloaded from the goods wagon and released from its protective wrappings we gazed on its magnificence as open mouthed as any of the gawping yokels who surrounded us. Imposingly tall, its lustrous black paintwork set off by discreet yellow coach lines and gleaming brass fittings, it seemed a chariot of the gods.

James had secured several carboys of motor spirit from a chemist’s shop in the High Street and, motioning the crowd to keep back (especially those who were smoking), he ceremoniously decanted the fluid into the fuel tank located at the back of the dashboard. He then made some mysterious adjustments – ‘You ’as to retard the ignition or it might start backwards loike,’ he explained – and, using all his considerable strength, swung the crank. At the second try the engine coughed noisily into roaring life and James hurried round to the driver’s seat to regulate it into a discreet chatter. Giving a small boy sixpence to return the carboys he motioned us ceremoniously aboard, closed the door and mounted the driver’s seat. With a growl and a splutter we were off – we were motoring!

The ten miles back to the village were accomplished in twenty minutes of blissful comfort compared to the long jolting of the pony trap. The brown leather seats cosseted us and the tall glass windows excluded the red Somerset dust – though James in the outside driver’s seat was swathed in it when he triumphantly opened the door on our arrival.

Later he explained the mechanical details of our new acquisition, and I will write down carefully what he said.

The car has a four-cylinder side-valve engine of 7.4 litres, and is rated at 35 horsepower under the French taxation system though in fact it will produce 45 at its maximum of 1200 revolutions per minute. It has electric ignition through a magneto but no other electrical components, and the head and tail lights are acetylene lamps, bright but sadly smelly. The engine drives the rear wheels through a leather cone clutch, a four-speed gearbox controlled by a sequential lever on the driver’s right side, and a modern differential gear – ‘No old-fangled chain droives for us,’ said James airily. There are cable-operated drum brakes on the rear wheels, an improvement on the previous model which had only a single brake acting on the transmission whose effect was described as ‘modest’.

The engine has previously been used in the successful Renault racing cars, which it would propel to more than 80 mph. With its heavier body our vehicle will not exceed 50, though that is more than exciting enough on bumpy country roads. On the flat the car will reach this speed in perhaps two minutes, and heavy application of the brakes will bring it to a stop in little more than 100 yards.

Comfort for passengers is assured by soft semi-elliptic springs on the front and rear axles, and the interior fittings are handsomely constructed in padded brown leather, Honduras mahogany and a tobacco brown long-pile carpet. The rear seat will hold two people in luxury or three who don’t object to a slight squash, and there are two folding seats that can be brought down from the partition behind the driver. Between these there is a little cabinet with holders for a cut glass whisky decanter, a soda syphon and six tumblers. The driver is also more comfortable than most who must endure an exposed front seat, as the radiator is set behind the engine and keeps his feet warm in the coldest weather. Hardy passengers can sit on his left.

The cloth-lined leather hood can be raised and lowered by two strong people in little more than ten minutes, though one must be careful to keep one’s fingers out of the mechanism.

James commented that the instruments are perhaps a little simple compared to the imposing array of dials in a Rolls-Royce. There is a speedometer on the front mudguard, mechanically driven by a flexible cable from one of the front wheels. The level of fuel is shown through a vertical strip of glass set into the dashboard-mounted tank above which are set five plungers for distributing oil to various parts. There are a hand throttle, a choke lever and an ignition timing lever for use when starting. Gear and handbrake levers are outside the body on the driver’s right. The clutch and brake pedals require a hefty push – no problem for the stalwart James. The steering, worked through a worm and sector mechanism, has considerable lost motion, and it is necessary to turn the steering wheel through about 15° before anything happens at the other end.

The car gives about ten miles to a gallon of fuel. We have installed a large tank in the stables and get periodic deliveries by horse and cart from Taunton.

We soon realised that we had overlooked something when we had our first puncture, an event to be expected as the country roads are littered with dropped horseshoe nails. We were delayed for three hours while James found a blacksmith and they laboriously disassembled the hub to remove the wheel, unglued the tyre from the rim, patched the hole, stuck the tyre back on with hot glue, reinflated it with great labour using a bicycle pump, the only one available, and refitted the wheel. How we wish we had spent a little more on wheels with the new detachable Michelin rims which can be removed from the wheel spokes by merely undoing eight bolts, and a replacement rim quickly fitted with its tyre already inflated.

The resourceful James had the answer to our problems as usual. He advised us to buy a ‘Stepney’ rim, a spare rim the same size as the car’s own wheels which can be strapped and bolted to the outside of a punctured wheel and holds it up well enough to allow you to drive home where your long suffering mechanic can repair the tyre later. This is not an ideal solution but it has saved us many an hour on the road. The spare rim is mounted vertically behind the right front mudguard, and James has to squeeze between it and the brake and gear levers to get into his seat.

The powerful engine carries the car to the top of Pitsford Hill in second gear, but we had an unpleasant surprise when visiting friends at Litton Cheney in Dorset. As the car climbed the notorious long 1 in 4 slope out of the village, on which many a carthorse has breathed its last, there was a smell of burning and a small explosion followed by clouds of steam gushing from the bonnet, and the car ground to a halt. James applied the handbrake and prudently put a stone behind each of the back wheels before he assessed the damage – a blown gasket. He explained that the cooling system works on the ‘thermosyphon’ principle: water heated by passing through the engine rises, flows to the radiator, and is here cooled so that it falls, keeping the circulation going without the need for a pump. But because the radiator is behind the engine, when the car goes up a very steep slope the flow of water stops, and this had allowed the engine to overheat. Nothing daunted, he unbolted the cylinder head – a simple task with a side-valve engine – used his penknife to cut a new gasket out a piece of linoleum supplied by a cottager, reassembled the engine and refilled the cooling system, and we were away in barely an hour. Such little mishaps are to be expected in the new adventure of motoring.

We sold the fractious Barack and didn’t get much for him. We still have a couple of hunters and ponies for the children, but the age of the horse is passing and soon this noble animal will be merely a creature for recreation. We are already seeing noisy tractors ploughing and harrowing the fields or towing carts of hay and silage.

Would I advise you to buy a motor car, dear readers? The answer is yes, at least if you are in possession of a comfortable income and have an assistant as capable as James. And if you do not, and opt for one of the many cheap machines that are coming on to the market, you will have pleasure mixed with frustration and liberally sprinkled with oil.

Copyright © Tachybaptus 2020

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file