Dedicated to all those who have served & those still serving.

19,000 British soldiers died on July 1st 1916, the first day of the Somme campaign.

© IWM. Full map can be seen here:- Burying the dead, Commonwealth War Graves Commission

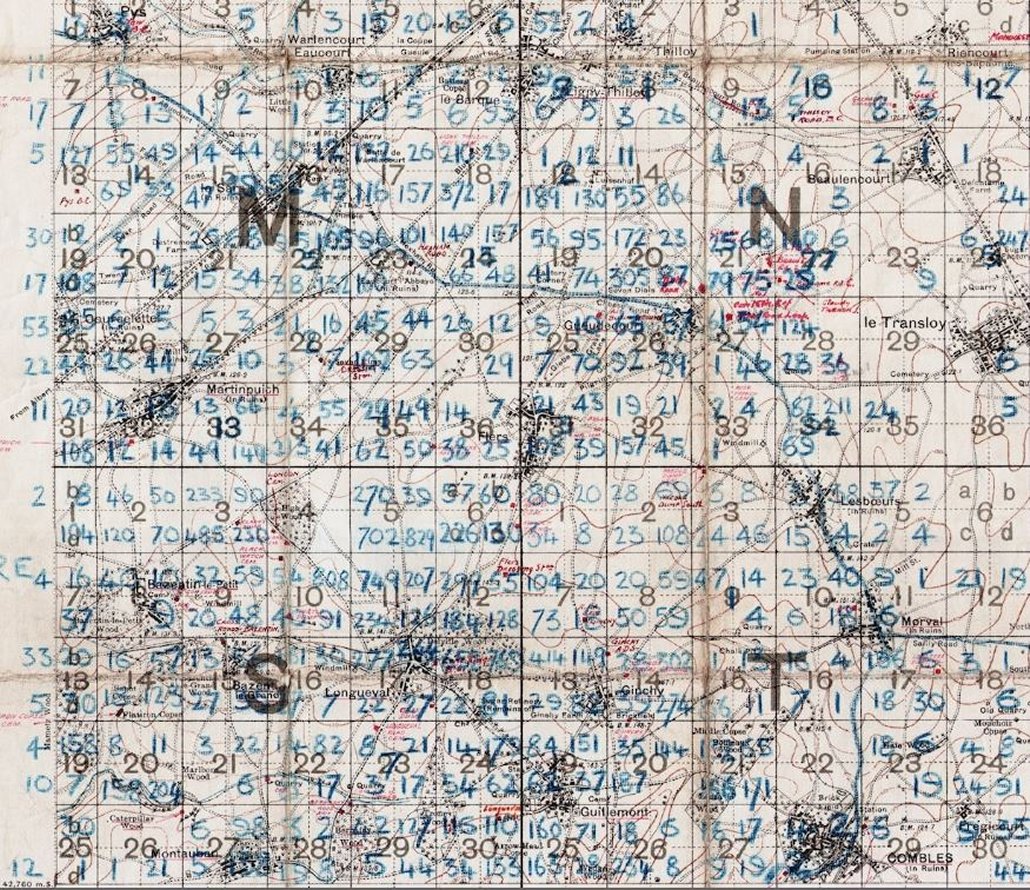

As well as marking and recording existing graves, the DGRE was tasked with searching for missing bodies, moving isolated graves or burial plots to larger cemeteries (a process known as ‘concentration’), and trying to identify bodies that were found or disinterred. The former battlefields were painstakingly divided into grids to be searched. These annotated maps record the number of known burials and temporary grave markers, to help the teams to find and remove them for reburial in a cemetery. The blue numbers do not include existing cemeteries or unburied bodies.

Body Density Maps like this one, which shows just the area around Delville Wood, were created later to record the number of known burials. The blue numbers on this section of a larger map refer to soldiers killed on the battlefield of the 1916 Somme battlefield. It is the work of Lieutenant Colonel Arthur Messer (Assistant Director of Graves Registration and Enquiries in France), who undertook to record the crosses of the Fallen on the battlefield, register their location, and then to re-inter the bodies together in larger cemeteries.

At first glance this detailed and dense map looks foreboding and somehow off-putting and that was before I comprehended what the numbers actually represented. What we are seeing here are pieces of four 6×6 grids (one complete and three partial) numbered 1-36, each one of these squares further subdivided into four section. Each larger square composed of 36 squares is 1000×1000 yards total, meaning that each one of the 36 subdivisions is about 166×166 yards, and each of the four segments of one smaller square is 83 yards. The blue numbers indicate a soldier killed on that field of battle which means that in the large 36-square “M” subdivision #18 that there were 210+29+372+17 fatalities, or 628 on a 166×166 yard field, or in one case 372 killed on a 83×83 yard plain. The deaths were even more intense on other areas of the field–in Square S #11 there were 749+207+234+126, or 1,416 deaths in that 166×166 yard field, and 749 on the 83×83 yard field. It is hard to visualize such loss, even more so when considering that these numbers represent just the bodies that were still intact after all the battles and fights in this area. The numbers would be a lot higher but for the constant shelling and fighting over the ground as so many bodies disappeared – literally vaporised by artillery shelling.

Extract from the diaries of Private J McCauley 1st Border Regiment…

“My old wounds were troubling me now that the cold weather had arrived, and I was suffering badly from frost-bitten feet. My hands had swollen to twice their normal size, and frequently my arms were completely numbed up to the elbows. For nearly a month I had not my boots off, and most of my companions were in the same miserable state as myself owing to the intense cold. I tried to imagine what would happen to us if the Germans attacked, but I recognised the probability that their physical condition was as bad as, if not worse, than ours. Putting the backs of my swollen hands to the barrel of my rifle I could feel nothing, and I could only lift it up by holding it between my elbows. God help us if we had been called upon to defend ourselves. Fifty yards away, the Germans were no doubt thinking the same thing. There came a day when the bitter cold and the pain of my wounds rendered me useless for fighting, and I was sent down the line. Again the scene of war changed for me, and I was destined to see war from another angle. I was attached to a company of about 150 men, and our task was to search for dead bodies and bury them. Two issues of raw rum were served out to us daily, to kill the dangerous germs which we might inhale. It was a ghastly job, and more than ever I learned what war meant. We commenced our grim work in the early morning, and set out in skirmishing order to search the ground. For the first week or two I could scarcely endure the experiences we met with, but gradually became hardened, and, for three months I continued the job. We worked in pairs, and our most important duty was to find the identity discs. After our morning’s work was over, a pile of rifles and barbed-wire stakes would mark the place where we had buried our gruesome discoveries. There they lay, English, German, Australians, South Africans, Canadians, all mingled together in the last great sleep.

Often have I picked up the remains of a fine brave man on a shovel. Just a little heap of bones and maggots to be carried to the common burial place. Numerous bodies were found lying submerged in the water in shell-holes and mine-craters; bodies that seemed quite whole, but which became like huge masses of white, slimy chalk when we handled them. The job had to be done; the identity disc had to be found. I shuddered as my hands, covered in soft flesh and slime, moved about in search of the disc, and I have had to pull bodies to pieces in order that they should not be buried unknown. And yet, what a large number did pass through my hands unknown. Not a clue of any kind to reveal the name by which the awful remains were known in life. It was painful to have to bury the unknown, be they British or German. Very often my chum and I would collect small stones and pebbles, and work out some epitaph above the grave, as a last worldly tribute to men who would probably be living today if the world had really striven for peace in the opening years of this century. In those three months I assisted in the burial of over ten thousand dead – known and unknown. The womenfolk of those thousands who may be yet mourning their loss in British and German homes can rest assured that we carried out our work with reverence and care for friend and foe.

For months after I relinquished this job the smell of the dead was in my nostrils. If only such scenes as we saw on the abandoned battle-grounds could be brought before the eyes of the peoples of this world, how nearer we would be brought to perpetual peace. But the world quickly forgets. I shall never forget.”

Christine McIntosh – Licence CC BY-ND 2.0

You can donate to The Royal British Legion here.

© DJM 2019

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file