She put the phone down and tried to get some sleep. Sam had reassured her that the body was dealt with, just needed them to take it to a place he knew, one of their bases here, where it could be disposed of, about an hour’s drive through the Cotswolds. She hadn’t dared ask what he had had to do. The guys there were friends, they would try to persuade him to stay with them of course, go back home, but almost certainly wouldn’t compel him, especially if she were there. Burn everything else first thing in the morning, including some of the carpets, his clothes and the bed linen, and drive over later, then back here for deep cleaning of the house and car. He was just so matter of fact about everything, but it wasn’t lack of intelligence she was sure, there was a streetwise wit there, a cunning imagination; she wondered what Sam might have been with a formal education.

She was feeling shaky still, drained by her switchback roller coaster ride of emotion; she just lay in the dark attempting to sleep, trying to move her mind on from recent events. She thought about him, how to approach him, the risks of having him live with her, his exposure to the mundane practicalities of her daily life, his potential disillusionment, his recovery. Her mind started wandering, free-wheeling away from her direction, images of tracing his scars, his wounds, with her finger tips, bringing him so close to her, beside her…

Don’t torture yourself.

Perhaps just this once, it’s better than the other images, those lurking just on the edge of visual imagination.

Don’t look.

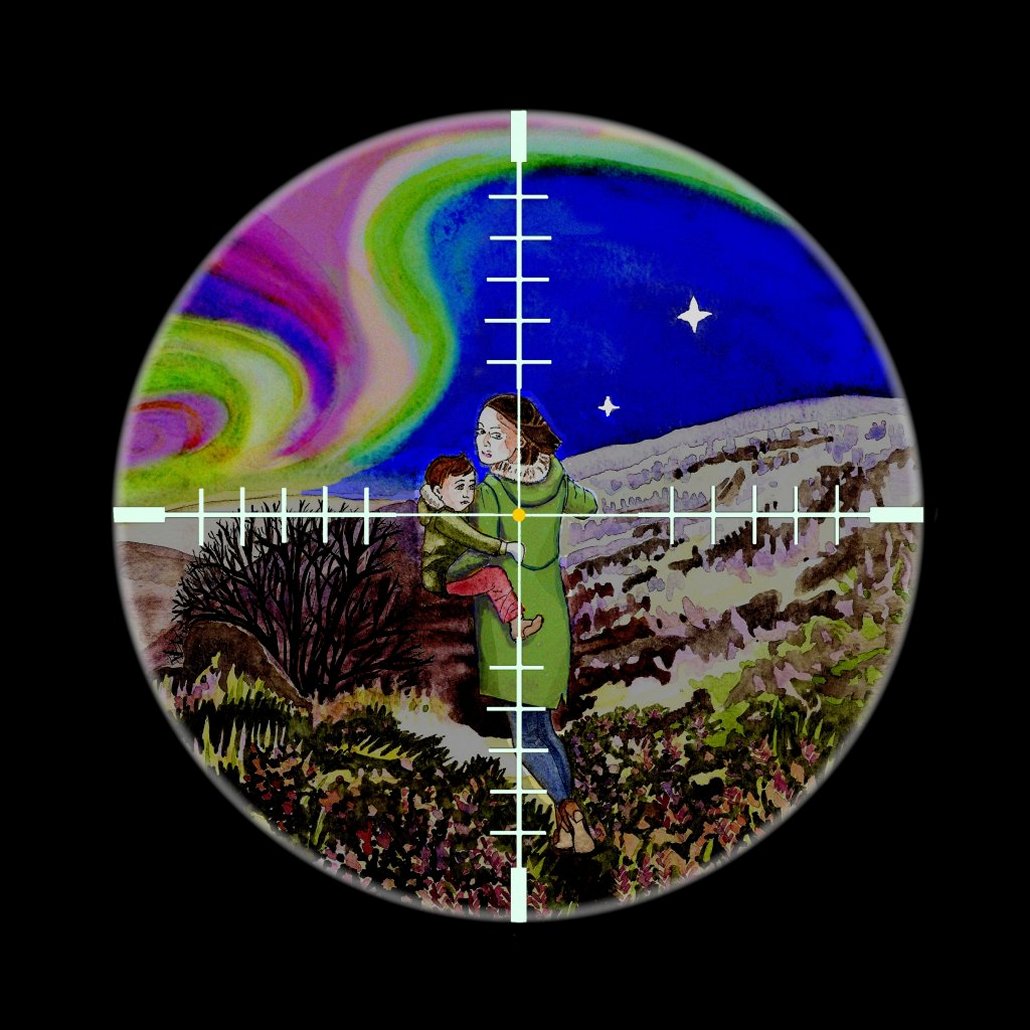

A tiny red dot growing into view, obscuring his fading image in her mind, blotting it out, a giant reddish orange hand, disembodied, fist clenched, just the index finger pointed straight at her accusingly, the tip of that finger expanding into the living picture of a bound and huddled man, pleading with her silently, stricken mute eyes communicating his terror, the flexing of her index finger, the recoil travelling up her wrist, once, twice, three times, four and finally the red spreading circles on his chest and head, something leaving him, reduced to an inanimate collection of dusty materials, blank eyes boring into her until she could stand it no longer and turned away, out-stared by a corpse. The end of that index finger extending, lengthening until it almost reached the bridge of her nose. She couldn’t retreat, was held frozen, helpless, like that man whose blood was coagulating around the shiny black plastic tomb. She was shaking, trembling under the effort to break its hold, get away, she was in the shadow of that hand now, swollen to monstrous proportions, beckoning her, and then he was there in between, breaking the spell, freeing her to move, but he was carrying another burden now, buckling under the strain, crimson with effort. She woke, bathed in cold sweat, tears coursing down her cheeks. As she sat up, almost retching, she pondered: just what have I done?

SATURDAY, SECOND WEEK AFTER EASTER

There, it was done, at least as far as he could manage; the execution was down to others now, a triumph of flexibility, reorganisation and improvisation. The reconnaissance completed, Monday it would be, late afternoon, when the number of those working at the two sites should be at its peak but when people were tiring at the end of the day, less alert hopefully. Twenty-four volunteers for London, fifty for Manchester, all that were left unless he waited at least another month to bring in more from overseas, but that was too risky. Weapons and explosives aplenty, over half those directly involved had previous experience, the outline plans devised, timings scheduled, but not too tightly: be prepared for the unexpected. He reached for the phone, time to inform those who thought themselves his masters what the plan was.

The four of them travelled down together, Sally, her son, Martha and Narin, the girl being almost certainly needed today; at least someone else on the train was as ridiculously over-dressed as she was. She found herself wondering if they had a decent dry-cleaner here for these gorgeous silks: of course not, she would have to ask Martha. She had tried to explain to Narin last night that the envoys might want to see her, learn how they could help. The girl had just nodded; looking resigned and then made them promise she wouldn’t have to leave if she refused. That promise had seemed to relax her, she was much more voluble afterwards, trying to speak in more expansive English, showing more interest in what was going on, and then the questions about Sam, how old was he, did he have a girlfriend, was he a soldier?

Martha just shrugged, answering truthfully. He was twenty-three, no he didn’t, he was in a way, she had never really thought about it like that before now. Why was he away when the others had come back? They didn’t know, it was a secret, his job. She seemed satisfied with that. Martha anything but, Sally could see.

It was clear that today’s business was being conducted in a very different manner, with specific issues being discussed, agreements secured, and plans formulated in small groups, just like Parliament’s committee stages back in Logres she thought, before coming up short: she was no longer thinking of it instinctively as home, had her loyalties shifted that far already? She felt like a spare cog even more than before, just sitting there by the group discussing the embassy to the Vatican, unable to contribute. After a couple of hours, the Abbot came over and asked her to follow him out and up to another room on the floor above.

“Is the girl Narin here?”

“Yes Father, as you asked. She wouldn’t come until we had promised that she wouldn’t be forced to leave. Is that alright?”

“Of course, no one is forced to leave. Now, my daughter, the Exarch wishes to meet with you for a few minutes with his translator, just to ask some questions, nothing you have not already been asked a hundred times since you joined us. And yes, I haven’t forgotten about your husband, that rash promise you extracted from us.”

He was smiling though.

In the room were the Exarch, a Greek translator, a couple of aides, the High Steward, the younger Thea, much more diplomatic than her mother Sally suspected, and one of the Abbot’s monks. She curtsied self-consciously, the Exarch laughed, asked her through the translator what she was doing. She blushed crimson with embarrassment, feeling a fool, explained it was an old mark of respect in her country. He smiled, thanking her, again through the translator. Then the questions, as the Abbot had said, nothing she was not now well practised at answering, then, out-of-the-blue: how did she feel about the Roman church, its pretensions, its schisms with other true Christians? He understood she was an Anglican?

How to answer that? It was like trying to navigate an unmarked minefield: we should focus on the future, not the past, what unites us, not the faults of our ancestors, overlook matters adiaphora, thanks Brother Peran for that, the Exarch’s eyes widened in approval, remember what the faith is for, try to forgive, unite whenever possible.

He looked at the Abbot as if asking whether she had been coached; the old man shook his head, beaming. The Exarch asked how she felt about leaving her young son for weeks, months, to end up serving as a minor aide in a world run exclusively by men who might not respect her.

His questions were the result of a sharp mind she realised, here was danger: if they refused to take her the Council’s promise about Andy would be void, she would be trapped here alone, forever.

She would do as she were asked, directed, by the Council in the interests of the greater good, a few slights were of little importance in the scale of things.

The High Steward smiled at that, the worry sloughing off him, the Exarch nodded, said that was all, she would do; they, He, had chosen well, and would she bring those beautiful robes with her to Rome? Had she others? She said she would, but that was all she possessed, a remarkable gift from Thea’s mother. No matter he said, more would be provided, she must be clothed to reflect the respect she is due as one of us, those who will forge a new alliance, repair old rifts. Moisture was in his eyes she could see, he really believed it, he wanted to mend history, heal ancient wounds.

The shock of what she was being asked to work on finally broke through, flooring her: no, she wouldn’t let them down. Later, she reflected, if there was one moment in which they had finally won her allegiance that was it; if they could get Andy here, there would be no pining to go back.

What about my parents, other family, can we get them here too? Just focus on the art of the possible, be practical.

That seemed to be it, the tension gone.

“Father, before I go… Narin? Can they help?”

“We had not forgotten child; she has been summoned.”

© 1642again 2018

Audio file