As a regular visitor to and buyer at auctions across the South of England I have become used to viewing lots and waiting for hours for the items I am interested in to come under the hammer. I now take along a book to read while the auctioneer wades through hundreds of lots before getting to the ones that particularly interest me. A surreptitious glance around the room will tell me if any of the regular faces that might be bidding against me are present but these days internet bidding can hide any number of oiks who may be sitting in the comfort of their warm homes and may well have probably have deeper pockets than yours truly. Auction houses now photograph all their lots and you can “view” on line which certainly avoids the necessity of viewing one day and then going back on another to bid. The problem with that is twofold. Many general auctioneers have little knowledge of the book market and will present a photo which just shows a “box of books” with only the top ones discernible or even worse with a long line of titles on a shelf, very few of which can actually be read even when magnified.

Thus it was I turned up to an auction in Sussex a couple of years ago tempted by the catalogue description for a number of lots which had been grouped together under the title of “from the library of John (Jack) Haines”. I have to admit that I knew nothing of Haines and it was only afterwards that I began to realise the significance of who Haines was and, more importantly, who he knew. More of this later.

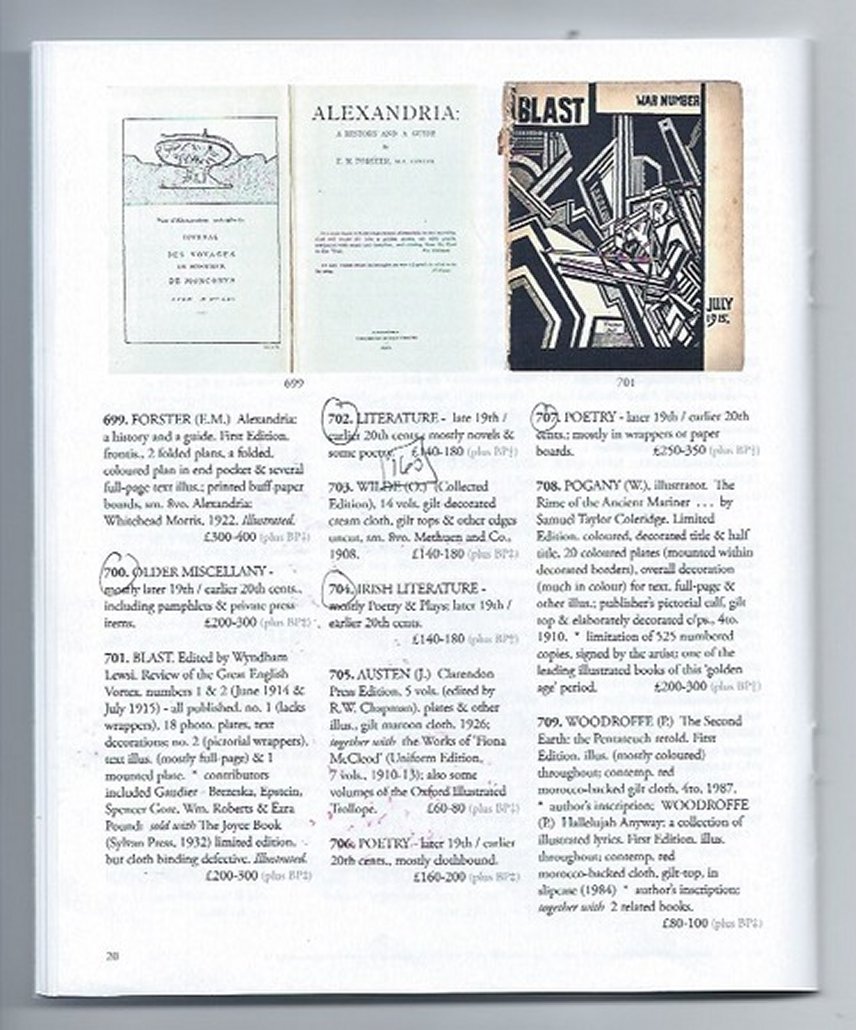

I was particularly interested in two large lots of poetry and prose (lots 704 and 707), one containing predominantly Irish material – Yeats, Synge, Dermot O’Byrne (Arnold Bax’s pseudonym, q.v. my little article on Arnold Bax on GP) etc – and another (707) which had a first edition of Gerard Manley Hopkins poetry collection buried in it, a very scarce item. The former was estimated at £140-£160, the latter at £250-£350. Calculating how much I wanted to pay for these lots in relation to how much I could realise a profit when listed separately I mentally fixed a bidding price of £400 for lot 704 and £500 for lot 707. In addition and very late in the viewing I took a look at lot 702 which was a very large collection of miscellaneous early 20th century literature. It had been put in one corner of the auction room and no-one else seemed to be taking much notice of it. Running my eye over the titles I could see some Thomas Hardy, Wyndham Lewis, John Freeman, Lascelles Abercrombie and other mostly minor stars in the early 20th century literary firmament. Worth a punt I thought at £200. We’ll see.

The auction began and thankfully this particular house limits their book section to a couple of hours so I didn’t have to wait long for the lots I was interested in to come up. Lot 702, the General Literature, knocked down to me for £160. OK, that’s fine but I saw it as a makeweight to the real stuff I wanted in lots 704 and 707. Lot 704 begins the bidding at £100 and I wave my paddle – as does someone else. We reach £200 and the bastard is still going and has a determined look about him. £300 passes and we are fast heading to my maximum bid. £400 is reached and passed and I make the cardinal error of all bidding at auctions, i.e. going beyond the top price I had wanted to pay. £420, £440, £460, £480…and my opponent bid £500. The next step was £550 and it was my bid choice. Was I going to push it? Nah. I backed out. At which point another bidder arrived and the two of them chased the price right up to £1500. Someone desperately wanted an item in that lot and I guessed it was a Yeats poetry collection in a very scarce dustwrapper.

Lot 707 arrived. Would I have a better chance with this collection? Having just been wiped out on 704 my guess was that the same bidders would be gunning for the same lot. And they did. My £500 bid was lost in the flurry of bidding and it was knocked down for £1200. Hey ho, I thought, you win some, you lose some but I was a bit deflated that all I had to take away from the auction was what I thought was a rather mediocre lot of what I now considered probably unsaleable literature. I boxed them up and put them in the boot of the car. Normally I would get books out and into my office immediately I got home but these I left in the boot for a couple of days before I felt I had the energy to wade through them.

When I sort through a collection of books I can normally and easily divide them into two camps. Those worth listing on line – Amazon or Abebooks – or those destined for the charity shop. In the old days I would list absolutely everything right up to the point that I found I could hardly move for the thousands of books kept in a storage unit. A first desperate cull removed all books priced at £5 and under quickly followed by those under £10 and then all large art books. Since then I have been brutal with listings and was prepared to ditch a fair number of this recent purchase. That is until I began to open up the books and found letters and notes that had been slipped in there by their former owner who, as we have read in the auction catalogue, was one Jack Haines and who had written his name in pencil on the front endpaper of most of the books. OK, let’s have a check on Jack Haines on line and see just who he was.

John (Jack as everyone called him) Wilton Haines, 1875-1960 was a minor poet, botanist, solicitor, confidante, and close friend of the Gloucestershire group of writers called the Dymock Poets who consisted chiefly of Robert Frost, Lascelles Abercrombie, Rupert Brooke and Edward Thomas. In addition Haines had influence within publishing circles and promoted many poets into getting published, including Ivor Gurney, another Gloucestershire poet, whom he also knew. And digging deeper into his history I found that he had been a good friend of Thomas Hardy and often visited him at Max Gate in Dorchester. Hold on a minute. Among the collection I had sorted out to be dropped into the charity shop was a book of Thomas Hardy poems – a book I have had way too many times before and always ended up in the “to be disposed” pile. If Jack Haines had written his name on the endpaper I could big it up in a listing and possibly find a buyer at £10 or so. I lifted it off the pile and as I did so a single sheet of paper fluttered from the closed pages.

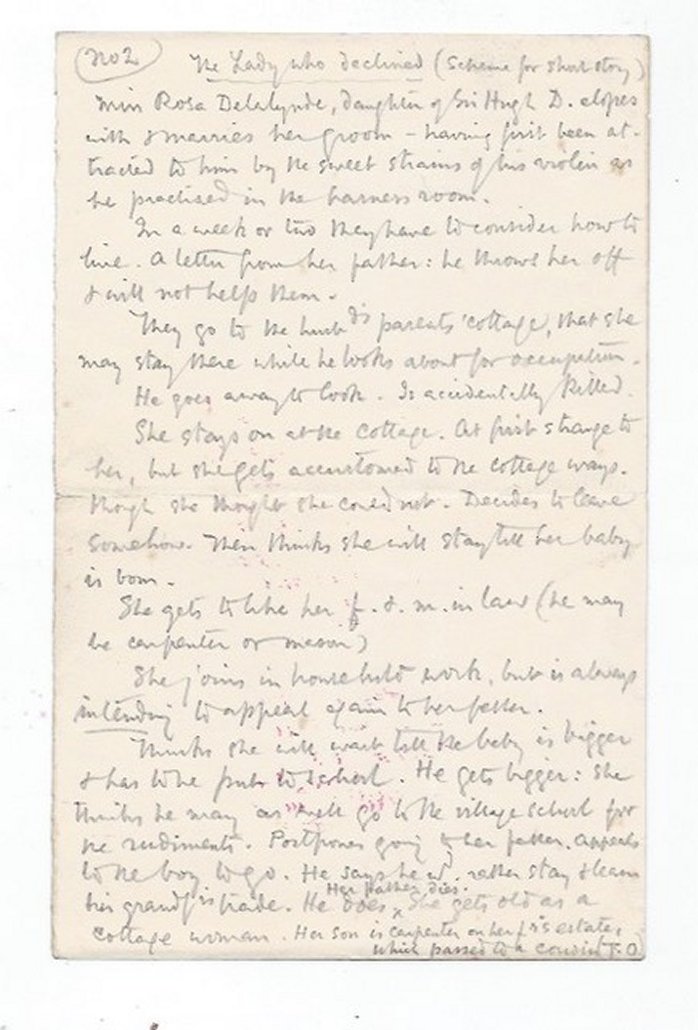

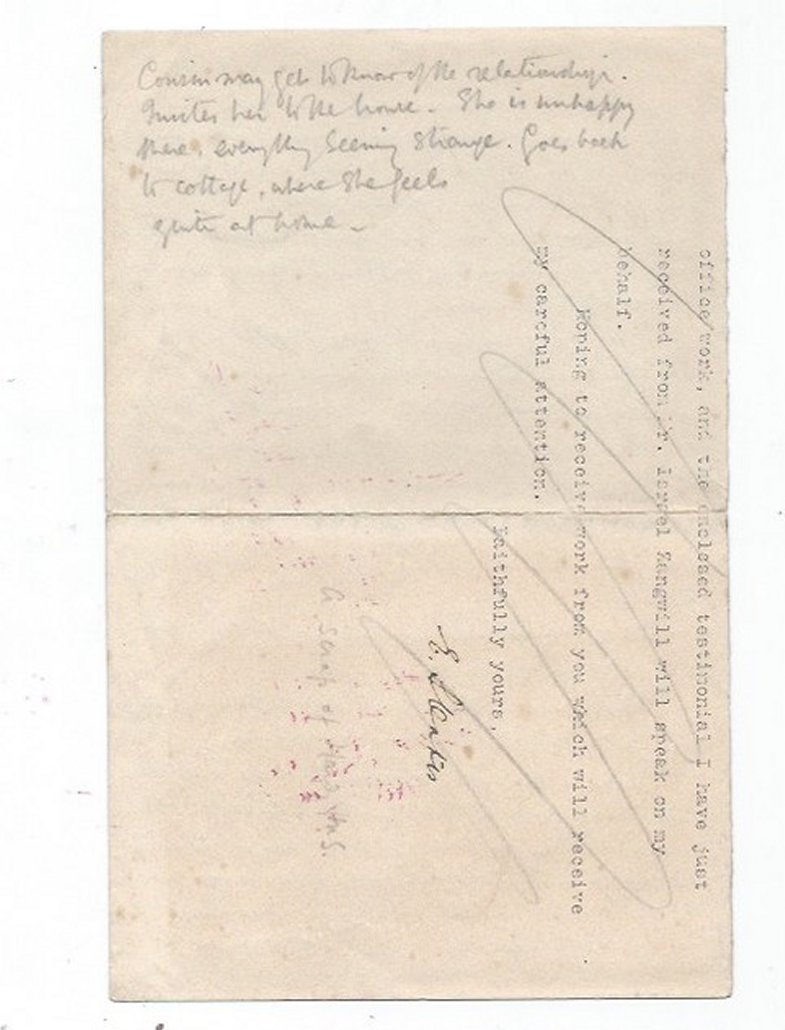

The page was no bigger than one you would find in a notepad but had been cut from a letter and had been written on both sides in pencil. It appeared to be a disjointed precis for a short story entitled “The Lady who Declined”. Intriguingly – and this is where the heart began to pump a little faster – someone had cryptically written “A scrap of Hardy ms.” on the reverse. Was this Hardy’s handwriting and was I looking at a precis for a short story that he never got round to finishing? How to check? Back when I began this bookselling lark I would have had to go to one of the big London auction houses or the British Library to try and get some verification of the author’s handwriting. Nowadays you just type “Thomas Hardy manuscript handwriting” into a search engine and bingo! up comes an example. Holding my scrap of ms. against the screen I quickly noticed very close similarities with confirmed Hardy handwriting but further research was needed. Contacting the Thomas Hardy Society in Dorchester I scanned the paper over to them and asked them the $64,000 question. Is this pukkah?

Yes, it was. The story “The Lady Who Declined” had been included in a bibliography compiled many years ago but it had been noted that it had never reached publication. The whereabouts of the ms was unknown or if it ever existed. Well, dear readers, I was holding the first draft of that story within my grubby and trembling fingers. How it had come to be sitting within the book of Hardy poems is a mystery but one has to presume that Hardy gave the book to Jack Haines as a present on one of his visits and had forgotten to check that he had stuffed his notes on the short story into the book. Had Haines not opened the book after he got it home? Surely he would have returned the notes to the author or did he only find them after Hardy died (1928) and decided to hang on to it as a memory of his friend? I knew I had a highly valuable piece of paper in my possession and offered it, in the first instance, to the TH Society but response came there none.

Within 48 hours of my listing it on Abebooks I was contacted by a devoted Thomas Hardy collector who knew a lot more about Jack Haines, Thomas Hardy and the Dymock Poets than I could ever glean from my researches on the internet. Would it be possible for me to send the Hardy notes to him to verify first-hand on the authorship? Some people you can just trust by talking and listening to them and this fellow sounded trustworthy. We agreed a price, he would send send me a cheque, let it clear and then I could send him the ms. with the proviso that monies and ms.could be returned if the handwriting proved inconclusive or fake. The deal was done and eventually I sent him, gratis, the Hardy book from which the ms. had dropped. He was delighted.

And so was I. The “find” paid for a week’s holiday for myself and Mrs A in Tenerife at a 5 star hotel.

© Roger Ackroyd 2020 – Roger’s book.

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file

Audio Player